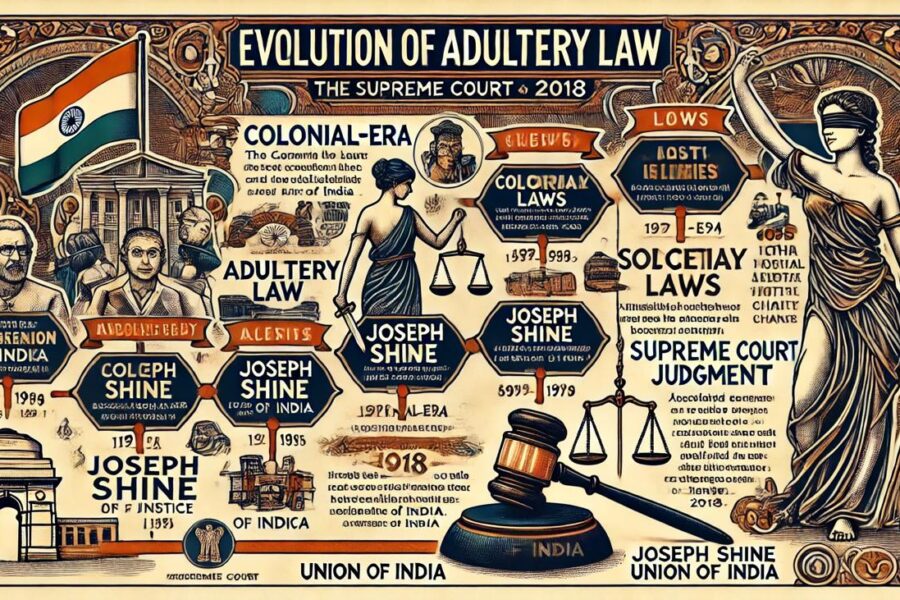

The evolution of the law concerning infidelity marks a significant chapter in the nation’s legal and social history. Over time, the legal treatment of adultery has undergone a dramatic transformation, culminating in a landmark judgment by the Supreme Court in 2018 that rendered adultery no longer a criminal offense. This monumental ruling reflects a broader shift toward personal autonomy, gender equality, and the protection of individual rights. Below is an overview of the development and eventual decriminalization of adultery law in India.

1. Pre-Independence Era:

Before India gained independence in 1947, the concept of adultery was largely governed by British colonial laws, primarily the Indian Penal Code (IPC) of 1860. The law on adultery was formulated during the British rule and largely reflected Victorian moral values.

- Section 497 of the IPC (1860): This section criminalized adultery and stated that a man who had sexual intercourse with a married woman without the consent of her husband would be guilty of adultery. However, the law did not hold women accountable. It did not consider a married woman who engaged in an adulterous relationship as an offender, and only the man was punished.

- Section 198 of the IPC: The law also restricted the initiation of adultery cases to the husband of the woman involved. It effectively left out the woman as an aggrieved party who could initiate legal action for adultery.

Thus, adultery was seen primarily as an offense against the husband, and the woman, even though involved in the act, was not considered criminally responsible under this law.

2. Post-Independence and Early Reforms:

After India gained independence in 1947, the IPC’s provisions, including Section 497, remained in force, and adultery continued to be treated as a criminal offense. The social and legal attitudes toward adultery remained largely influenced by traditional views that prioritized family honor and the protection of marriage.

Over the decades, there were few significant reforms or debates surrounding this issue, and the law continued to reflect patriarchal norms.

3. Modern-Day Developments:

In the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st century, the legal and societal understanding of adultery began to change. There were growing calls for reform, particularly because the existing law treated women as passive subjects and perpetuated gender inequality.

Key Legal Developments:

- 2014: Law Commission of India Report: The Law Commission of India, in its 243rd report (2014), recommended the decriminalization of adultery, citing that adultery should be treated as a civil matter rather than a criminal offense. The Commission argued that criminalizing adultery was an infringement on individual freedoms and privacy and that marriage should be seen as a personal relationship, not one to be controlled by the state.

- 2018: The Landmark Supreme Court Judgment (Joseph Shine v. Union of India): In a landmark decision on September 27, 2018, the Supreme Court of India struck down Section 497 of the Indian Penal Code, declaring it unconstitutional. This judgment was a major step forward for women’s rights and gender equality in India.

In the Joseph Shine v. Union of India (2018) judgment, the Supreme Court of India struck down Section 497 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), which criminalized adultery. The Court ruled that this law was unconstitutional, as it violated the right to equality (Article 14) and the right to privacy (Article 21) guaranteed by the Constitution. The judgment was a landmark ruling that decriminalized adultery, while still allowing it to be a ground for divorce.

Here are key provisions under the new legal context following the 2018 ruling:

1. Striking Down Section 497 IPC:

The Court declared Section 497 of the IPC unconstitutional, which made adultery a criminal offense and only punished men for committing adultery with a married woman, leaving the woman out of the scope of the law.

- Justice Chandrachud (writing for the majority):

“The provision is archaic and patently unconstitutional… It is the right of an individual, whether male or female, to be treated as an equal before the law and not as a lesser being.” - Justice Chandrachud further elaborated:

“By treating the woman as a property of the man, Section 497 relegates her to the status of a ‘chattel’. It violates the Constitution’s promise of equality before the law.”

2. Gender Inequality and Constitutional Rights:

One of the main arguments for striking down Section 497 was the inherent gender inequality in the law. Women were not held accountable for adultery, and the law did not treat them as equal participants in marital relationships.

- Justice Nariman (in his concurring opinion):

“The law under Section 497 IPC treats women as chattel, as a mere property of the husband. Such a provision is discriminatory and violates the fundamental rights of equality and dignity, as enshrined in Articles 14, 15, and 21 of the Constitution.” - Justice Chandrachud emphasized:

“Adultery, though immoral, does not concern itself with criminality but with personal autonomy. Criminal law should not intrude on the privacy of individuals in such intimate relationships.”

3. Right to Privacy:

The Court linked the issue of adultery to privacy rights, asserting that the law should not interfere with consensual adult relationships.

- Justice Chandrachud wrote:

“Adultery can be a ground for divorce but it should not be criminalized… It is not the function of criminal law to regulate consensual sexual relationships between adults.” - He further stated:

“The Constitution recognizes the right of an individual to make personal choices and decisions. Criminal law should not regulate personal relationships unless there is a clear violation of public order or harm to society at large.”

4. The Impact of the Judgment:

The judgment not only decriminalized adultery but also emphasized that the state should not interfere with personal autonomy within relationships.

- Justice Chandrachud concluded:

“Marriage is a personal relationship between individuals. The Constitution protects the dignity of individuals and accords them the freedom to live their lives according to their choice, free from the dictates of the state.”

5. Provisions Under the New Law (Post-2018 Judgment):

With the decriminalization of adultery, the provision under Section 497 of the IPC no longer applies. The change brought about by the ruling can be summarized as:

- Adultery is no longer a criminal offense under the Indian Penal Code.

- However, adultery remains a ground for divorce under civil law provisions:

- Hindu Marriage Act (1955): Section 13(1)(i) allows a spouse to seek divorce on the grounds of adultery.

- Special Marriage Act (1954): Section 27(1)(a) also allows a spouse to file for divorce if the other party has committed adultery.

- Christian Marriage Act (1872): Adultery is a ground for divorce under Section 10 of this Act.

- Civil remedies: While adultery is no longer punishable by law, it can influence divorce proceedings, alimony, or custody of children. A person can present evidence of adultery to strengthen their case for divorce or as part of a broader claim in family law matters.

6. Legal and Societal Impact:

While the judgment removed the criminal sanctions for adultery, it did not remove the moral and social implications of the act. The Supreme Court in its ruling emphasized the need for a progressive society, which respects individual autonomy and treats both spouses equally.

- Justice Nariman stated:

“A law which criminalizes adultery, which is nothing but a violation of the sanctity of marriage between two consenting adults, is against the spirit of the Constitution. It represents an outdated notion of marriage and personhood.”

This judgment was hailed as a significant victory for women’s rights and the protection of individual freedoms. The judgment overturned Section 497 of the IPC, which had criminalized adultery and treated women as secondary actors in marital relationships. It recognized that the institution of marriage and sexual relationships between consenting adults should be free from state interference, and that a relationship should not be criminalized. Despite this, adultery remains a ground for divorce, and its social and moral significance remains.

4. Post-2018 Developments:

Since the 2018 Supreme Court ruling, adultery is no longer a criminal offense in India. However, it remains a ground for divorce in civil law. Some of the consequences and implications of this change include:

- Divorce Proceedings: While adultery is no longer a criminal offense, it remains a valid ground for divorce under Section 13 of the Hindu Marriage Act (1955) and similar provisions under other personal laws. A spouse can seek divorce on the grounds of adultery, and the courts will consider it as a factor in granting divorce.

- Adultery in Civil Context: Although adultery is no longer punishable under criminal law, it continues to have social and moral significance, especially in divorce cases or where it leads to issues like domestic violence or child custody disputes.

5. Impact of the Judgment:

The 2018 judgment on adultery reflects broader societal changes in India, including:

- Progressive Legal Thought: The ruling represents a shift toward more progressive and gender-equal laws that recognize the autonomy of individuals, including women, within the marriage.

- Equality and Privacy: It highlights the Court’s growing recognition of personal freedoms, the importance of privacy in personal relationships, and the need for equality in the law.

- Debate on Morality and Law: While the judgment was widely seen as a positive development for personal freedoms, some sections of society still hold conservative views, and there remains debate about the morality of adultery and the role of the law in regulating personal conduct.

Conclusion:

The development of adultery law in India reflects a shift from colonial-era provisions to a more progressive, gender-sensitive approach, particularly with the 2018 decriminalization of adultery. This has been a significant step in the country’s legal history, aligning with broader movements for gender equality and individual rights. The law now treats adultery as a personal matter rather than a criminal offense, while still allowing it to be addressed in civil matters such as divorce.