What is Defamation?

Defamation means saying or writing things about someone that aren’t true and harm their reputation in the eyes of regular people. If someone purposely says or publishes false and harmful statements to ruin someone’s reputation, it’s called defamation, and it’s against the law. A person’s reputation is like their own possession, and harming it can lead to legal consequences. Defamation can happen through words (spoken) or in writing (written). When false things are written, like in printed material or images, it’s called libel, and if spoken, it’s called slander.

Defamation’s roots are found in Roman and German legal systems. Romans deemed offensive chants worthy of capital punishment, while early English and German laws sanctioned insults with tongue removal. By the late 18th century, England only considered imputation of crime or social disease as slander, expanded later by the Slander of Women Act. French defamation laws were strict, penalizing prominent retractions in newspapers severely, permitting only truth as a defense for publications about public figures. In Italy, defamation is a criminal offense, where truth rarely serves as a valid excuse for defamation.

Defamation Laws in India

Citizens enjoy various freedoms under Article 19 of the Constitution, but Article 19(2) introduces reasonable restrictions on freedom of speech and expression outlined in Article 19(1)(a). Exceptions include contempt of court, defamation, and incitement to an offense.

Defamation is actionable under both civil and criminal law. In civil cases, it falls under the Law of Torts, resulting in damages awarded to the claimant. In criminal law, defamation is a bailable, non-cognizable, and compoundable offense. A police officer can only arrest with a magistrate-issued arrest warrant. The Indian Penal Code prescribes a simple imprisonment of up to two years, or a fine, or both as punishment for defamation.

Civil Defamation

For a successful defamation case, false statements must harm someone’s reputation without their consent. The harmful content should be designed to damage the reputation of an individual or a group, exposing them to hatred, contempt, or ridicule. The evaluation of whether it damages reputation should be based on how an average person perceives and understands the matter.

Additionally, the statements should specifically target an individual or a group; general claims like “all politicians are corrupt” are too broad for compensation.

The false statement must be communicated to a third party, either spoken or written, for defamation to occur. If a letter is sent in an unknown language, requiring someone else to read it, any defamatory statement in it still constitutes defamation, even if it was sent as a private letter, as the involvement of a third person was necessary to read it. Monetary compensation can be sought from the defendant in such defamation cases.

If all these criteria are met, a defamation case can proceed successfully. The accused can present defenses, arguing that the statement they published was true, or that their comments were fair and in the public interest, grounded in true events. Some individuals have the privilege to make statements, even if they are defamatory, such as those involved in judicial proceedings or members of parliament. If the defendant cannot prove their actions, the lawsuit is deemed successful.

Criminal Defamation

Essentially, it’s a form of defamation that could lead to imprisonment. In criminal cases, proving intent to defame is crucial. The accusation must be made with malicious intent to harm someone’s reputation, or at least with the knowledge that the publication is likely to do so. It must be established beyond a reasonable doubt that the action was intended to lower another person’s reputation.

Section 499 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, outlines defamation and its exceptions. Any words or signs intentionally imputed to cause harm, or with the knowledge that harm will result, may constitute defamation. Even imputations against a deceased person could be defamatory if they would have harmed the person’s reputation while alive. This extends to entities like companies or associations. Defamation only occurs if the alleged statement directly or indirectly diminishes the moral, intellectual character, or respect for caste or calling in the eyes of others.

Exceptions:

People making defamatory statements can be exempt from punishment if they fit into one of the ten exceptions outlined in Section 499. These include:

1. Stating any truth made for the public good, although truth is rarely a defence unless for public benefit.

2. Expressing opinions in good faith about the conduct of a public servant in the discharge of their public duties.

3. Offering opinions in good faith about the conduct of any person related to a public question.

4. Publishing true reports of court proceedings or their outcomes is not considered defamation.

5. Forming opinions in good faith about the merits of a civil or criminal case decided by a court or the conduct of individuals involved in that case.

6. Expressing opinions about the merits of any performance presented for public judgement or about the author is not defamation if done in good faith.

7. Passing censures in good faith by individuals without authority over others is not defamation. Censure involves formally expressing severe disapproval.

8. Accusing someone of an offense to a person with lawful authority over the accused in good faith is an exception to defamation. Examples include complaints about servants to masters and children to parents.

9. Making statements about the character of a person is not defamation if done to protect the interests of the person making the statement, another person, or for the public good.

10. Conveying cautions to one person about another is not defamation if intended for the well-being of the recipient or another person, or for the public good.

Constitutionality of Defamation Laws

Debates have arisen regarding defamation laws being seen as a breach of the fundamental right protected by Article 19 of the Constitution. The Supreme Court has affirmed that the criminal aspects of defamation align with the constitution and do not contradict the right to free speech. The court emphasised that while freedom of speech and expression is highly revered, it is not without limitations. The right to life, as defined in Article 21, encompasses the right to one’s reputation and should not be undermined by the free speech rights of others.

Role Of Media

The media is acknowledged as the fourth pillar of society, alongside the executive, legislature, and judiciary. In the modern era, media has gained significant importance in various aspects of our economy, particularly in shaping public opinion. Newspapers, television, the Internet, and other sources keep us connected with the media.

As a result, envisioning life without the media in the present time is nearly impossible. It has become a crucial component of our daily existence, and our lives would feel incomplete without it. Effective laws are necessary to regulate the operations of the media.

Who is a celebrity?

In Titan Industries Ltd. vs. Ramkumar Jewellers (2012), the Delhi High Court defined a celebrity as “a famous or a well-known person and is merely a person to whom many people talk about or know about.” The court also stated that “the right to publicity” is the right to control the commercial use of a person’s identity.

Privacy in India

The Information Technology Act (ITA) of 2000 stands as India’s most extensive legal framework concerning internet privacy. The ITA includes regulations that offer some protection for online privacy in certain situations but may compromise it in others. Notably, the ITA does not address issues such as the legal standing of social media content in India, the merging and sharing of data across databases, the transmission of images of one’s “private parts” on the internet, whether users have the right to be informed about cookies and do-not-track options, and the use of electronic personal identifiers. The legislative gaps in the ITA contribute to a gradual erosion of online users’ privacy.

Celebrities often become subjects of personalization, with the public displaying curiosity about every aspect of their lives, from personal affairs to trivial details like clothing, cosmetics, and places visited. Due to the distant nature of celebrity-personal audience relationships, there is no inherent exchange of information. Consequently, celebrities strive to keep their personal details confidential to avoid potential embarrassment, shame, and feelings of insecurity.

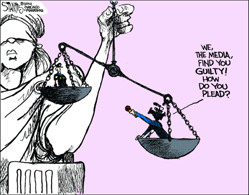

Media trials vs. Judiciary

No legal system permits the media to conduct trials. Media trials and journalism have two sides. Sometimes, journalists create a predetermined image of an accused, damaging their reputation and potentially influencing the trial and judgment. Media trials have become more significant in India, with instances where the media takes the case into its own hands, passing judgments against the accused and undermining fair trials in court. The media can influence people’s thinking, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic when news channels focused on deaths and new cases, instilling fear, while emphasizing recoveries could motivate and contribute positively. The media shapes people’s perceptions, bringing both positive and harmful effects.

Cases regarding Media Trials

The Case of Dr. Rajesh Talwar and another vs Central Bureau of Investigation case in 2013 grabbed significant media attention and remained in the headlines for an extended period. In May 2008, the tragic murder of Arushi and her domestic helper Hemraj occurred. Initially, a large number of names were on the suspect list. The media coverage was widely perceived as a trial by media, making scandalous claims against Aarushi and other accused individuals. Despite lacking reliable evidence, the media questioned Arushi’s character and her relationship with Hemraj. In November 2013, the parents were convicted of the murder and received life sentences. Many critics argued that the case relied on weak evidence, insufficient to conclusively implicate the parents, with other potential suspects overlooked. The media trial further fueled public doubts. The Talwars appealed the verdict, leading to their acquittal by the Allahabad High Court in 2017, which granted them the benefit of the doubt and considered the evidence insufficient.

The Bombay High Court ruled in the Sushant Singh Rajput death case that the media should refrain from covering ongoing investigations and current events that serve the public interest instead of what they think the public wants to hear. Although not all reports on the list are likely to cause prejudice to an existing investigation, it was established by the ruling.

The following are some examples:

For instance, in cases of suicide, presenting the deceased as weak or violating their privacy is not allowed. Character assassination, tarnishing a person’s reputation, and making disparaging remarks about the accused during an ongoing inquiry are also prohibited. Engaging in interviews with victims, witnesses, or their families, revealing crucial witness versions, and publishing confessions allegedly made to police officers without explaining the intricacies of the Evidence Act,1872 are restricted. Additionally, printing images of an accused for easier identification, prematurely deciding on guilt or innocence, forecasting future actions, and leaking sensitive investigative data are not permissible. Operating against the terms of the programme Code outlined in Section 5 of the Cable TV Network Act and Rule 6 of the Cable TV Network Rules may lead to contempt of court. The bench emphasizes that while these guidelines are indicative, any media report must adhere to the Programme Code, journalistic standards, and the Code of Ethics and Broadcasting Regulations to avoid regulatory action.

Conclusion

From printed publications like the Bengal Gazette to digital ones, media has changed and evolved over time. India does not have a specific law safeguarding press freedom, in contrast to the US. For the media to function freely, political influences and restrictions must be removed. In a perfect world, it wouldn’t have to base editorial decisions on audience, sponsors, or ratings.

Everyone can benefit from having a good reputation. Any harm done to such an asset can be resolved lawfully. Laws against defamation were passed in order to stop people from maliciously exercising their right to free speech and expression. It is appropriate that Indian law does not distinguish between slander and libel. If there hadn’t been a written publishing of the matter, there would have been opportunities for defamation and legal escape.

Discussing ongoing cases through debates or conversations is fruitless since many of these disputes lack evidence and await a genuine legal trial outcome. In today’s information-rich environment, there’s an inherent pressure to stay active on television and other media platforms. Striking a balance in regulating the media without compromising its democratic purpose in a highly competitive landscape poses a challenge. The question arises: who should be responsible for enforcing these limitations?

While allowing the media to report news is essential, when it comes to interference with the legal system, the judiciary can establish fair regulations. These restrictions shouldn’t compromise reporting quality but must define crucial boundaries, particularly in sensitive instances in India, to prevent media trials.

Quick service without compromising on quality.

order generic zestril without insurance

They always prioritize the customer’s needs.

http://semaglupharm.com/# Semaglu Pharm

lipitor black box warning Lipi Pharm lipitor and breast cancer

how can i get prednisone: prednisone 50 mg tablet cost – prednisone cost in india

Lipi Pharm: LipiPharm – Order cholesterol medication online

https://semaglupharm.com/# Semaglu Pharm

https://semaglupharm.com/# effects of semaglutide

prednisone 60 mg daily buy prednisone 40 mg generic prednisone pills

Predni Pharm: order prednisone – brand prednisone

SemagluPharm: Semaglu Pharm – Semaglu Pharm

Online pharmacy Rybelsus goodrx semaglutide SemagluPharm

Crestor Pharm: Over-the-counter Crestor USA – Buy statins online discreet shipping

Semaglu Pharm: jardiance and rybelsus – п»їBuy Rybelsus online USA

http://semaglupharm.com/# SemagluPharm

Crestor 10mg / 20mg / 40mg online CrestorPharm Crestor home delivery USA

No prescription diabetes meds online: online rybelsus – SemagluPharm

Semaglu Pharm: compounded semaglutide cost – how fast does semaglutide work for weight loss

Lipi Pharm: Order cholesterol medication online – canadian pharmacy lipitor

FDA-approved generic statins online Lipi Pharm FDA-approved generic statins online

Crestor Pharm: CrestorPharm – crestor other names

https://lipipharm.shop/# Lipi Pharm

rosuvastatin dose for adults: crestor otc – Online statin therapy without RX

Predni Pharm PredniPharm purchase prednisone from india

PredniPharm: Predni Pharm – prednisone 10mg for sale

Online statin drugs no doctor visit: atorvastatin 40 mg coupon – Lipi Pharm

LipiPharm atorvastatin 20 mg price without insurance LipiPharm

Lipi Pharm: LipiPharm – atorvastatin en espaГ±ol

PredniPharm: PredniPharm – prednisone

Semaglu Pharm FDA-approved Rybelsus alternative Semaglu Pharm

https://semaglupharm.shop/# Rybelsus 3mg 7mg 14mg

berberine and crestor: Rosuvastatin tablets without doctor approval – does crestor cause brain fog

https://semaglupharm.shop/# can you switch from semaglutide to tirzepatide

Rybelsus for blood sugar control: Semaglu Pharm – SemagluPharm

Predni Pharm buy prednisone online no prescription Predni Pharm

SemagluPharm: Rybelsus 3mg 7mg 14mg – Order Rybelsus discreetly

PredniPharm PredniPharm PredniPharm

LipiPharm: Cheap Lipitor 10mg / 20mg / 40mg – Lipi Pharm

https://semaglupharm.com/# is rybelsus a glp 1

prednisone brand name canada: PredniPharm – PredniPharm

PredniPharm PredniPharm Predni Pharm

https://semaglupharm.com/# Semaglu Pharm

rybelsus for obesity: semaglutide manufacturer – Rybelsus online pharmacy reviews

best price rosuvastatin 10 mg: crestor and memory loss – CrestorPharm

PredniPharm Predni Pharm PredniPharm

http://lipipharm.com/# LipiPharm

canadian pharmacy king Canada Pharm Global canadianpharmacyworld

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: Meds From Mexico – medication from mexico pharmacy

best rated canadian pharmacy: Canada Pharm Global – legitimate canadian pharmacy online

Meds From Mexico: buying prescription drugs in mexico – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

india online pharmacy India Pharm Global pharmacy website india

http://medsfrommexico.com/# mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

cheapest online pharmacy india: India Pharm Global – India Pharm Global

Meds From Mexico: Meds From Mexico – Meds From Mexico

canadian pharmacies legitimate canadian online pharmacies my canadian pharmacy rx

reliable canadian pharmacy: Canada Pharm Global – canadian pharmacy near me

India Pharm Global: reputable indian online pharmacy – India Pharm Global

https://medsfrommexico.com/# Meds From Mexico

Meds From Mexico Meds From Mexico mexican mail order pharmacies

online shopping pharmacy india: best india pharmacy – cheapest online pharmacy india

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies mexican rx online mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

indianpharmacy com: India Pharm Global – online shopping pharmacy india

India Pharm Global: India Pharm Global – India Pharm Global

https://canadapharmglobal.com/# legitimate canadian pharmacies

canada drugstore pharmacy rx canadian drug pharmacy canadian family pharmacy

https://canadapharmglobal.shop/# canadian pharmacy scam

India Pharm Global: indian pharmacy paypal – top online pharmacy india

mexico drug stores pharmacies: mexican pharmaceuticals online – Meds From Mexico

Meds From Mexico mexican drugstore online Meds From Mexico

top 10 pharmacies in india: India Pharm Global – India Pharm Global

reputable indian online pharmacy: India Pharm Global – india pharmacy mail order

https://canadapharmglobal.com/# best canadian pharmacy

India Pharm Global mail order pharmacy india best online pharmacy india

canada pharmacy world: Canada Pharm Global – canadian pharmacy uk delivery

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa reputable mexican pharmacies online medicine in mexico pharmacies

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – purple pharmacy mexico price list

farmacias gran canaria: Papa Farma – venta farmacias madrid

http://papafarma.com/# farmasdirect

beställa hem recept från apoteket tandskydd apotek apotek universitet

Rask Apotek: tannkrem apotek – hente resept pГҐ annet apotek

pomata desamix effe: EFarmaciaIt – EFarmaciaIt

Rask Apotek dГёgnГҐpent apotek Rask Apotek

farmacia salute e benessere: farmacia con scalapay – EFarmaciaIt

https://efarmaciait.com/# farmacia on line spedizione gratuita

Svenska Pharma: Svenska Pharma – starta apotek

Papa Farma Papa Farma farmacia 24 h valencia

alunstift apotek: apotek brГ¶stpump – sola med kokosolja

på nätet värmekudde apotek Svenska Pharma

EFarmaciaIt: crema fucidin prezzo – EFarmaciaIt

EFarmaciaIt: vessel 250 uls miglior prezzo – augmentin deutsch

https://efarmaciait.com/# cilodex bambini

eksem hund bilder Svenska Pharma Svenska Pharma

farmacia 24h zaragoza: movicol pediГЎtrico sin receta – cialis 10 mg 4 comprimidos precio

dodot 3×2: Papa Farma – farmacia ds

sink apotek: Rask Apotek – Rask Apotek

tiche 150 mycostatin neonato crema travocort a cosa serve

https://raskapotek.com/# apotek resept pГҐ nett

Rask Apotek: Rask Apotek – Rask Apotek

svovelkrem apotek: Rask Apotek – Rask Apotek

EFarmaciaIt 1000 farmacie offerte EFarmaciaIt

Svenska Pharma: kanyler apotek – e apotek

apotek vaksine online apotek Rask Apotek

http://raskapotek.com/# Rask Apotek

vibradores embarazo: farmacia b – Papa Farma

Papa Farma: Papa Farma – Papa Farma

Svenska Pharma Svenska Pharma Svenska Pharma

apotek spruta: Svenska Pharma – Svenska Pharma

mycostatin oral: diferencia entre parafarmacia y farmacia – recambios cepillo oral b

elocom prospecto farmacia online envГo gratis valencia farmacias cercanas a mi ubicaciГіn

http://papafarma.com/# Papa Farma

varmepute med ris apotek: kladd apotek – Rask Apotek

beste nettapotek: Rask Apotek – Rask Apotek

Rask Apotek Гёrerens apotek Rask Apotek

glukose apotek: vitamin a syre krem apotek – Rask Apotek

ryaltris nasal spray prezzo online farmacia EFarmaciaIt

PharmaJetzt: apotheken shop online – PharmaJetzt

international online pharmacy claritin d pharmacy propranolol pharmacy uk

PharmaJetzt: PharmaJetzt – PharmaJetzt

buy provigil online pharmacy: clozaril pharmacy registry – no prior prescription required pharmacy

https://medicijnpunt.shop/# Medicijn Punt

Medicijn Punt farmacia online MedicijnPunt

Medicijn Punt: apotheek apotheek – MedicijnPunt

Pharma Connect USA: PharmaConnectUSA – AebgJoymn

cymbalta pharmacy prices PharmaConnectUSA PharmaConnectUSA

PharmaConnectUSA: Pharma Connect USA – PharmaConnectUSA

Pharma Jetzt: PharmaJetzt – online apotheke bad steben

https://pharmajetzt.com/# Pharma Jetzt

Medicijn Punt MedicijnPunt online medicijnen bestellen

caudalie anti tache avis: amoxicilline 500 enfant – Pharma Confiance

Pharma Connect USA: PharmaConnectUSA – the medicine store pharmacy

apotheke im internet Pharma Jetzt shopaphotheke

online lortab pharmacy: online pharmacy discount – generic viagra us pharmacy

https://pharmaconnectusa.shop/# viagra overseas pharmacy

Pharma Confiance: cialis 20 mg achat en ligne – hГ©morroГЇdes traitement efficace avis

https://pharmaconnectusa.shop/# priligy uk pharmacy

Pharma Connect USA sam’s club pharmacy hours PharmaConnectUSA

viagra in indian pharmacy: propecia pharmacy2u – Glucophage SR

united healthcare online pharmacy: dutasteride from dr reddy’s or inhouse pharmacy – pharmacy rx

Pharma Jetzt PharmaJetzt Pharma Jetzt

Pharma Confiance: pansement pour chat tГЄte – Pharma Confiance

vacuum medintim: fleurs de bach livre – Pharma Confiance

https://pharmajetzt.com/# apotheken produkte

medicijn apotheek online nl Medicijn Punt

shop apotheke medikamente: shop apotheke berlin – PharmaJetzt

dog pharmacy online: Pharma Connect USA – online pharmacy generic viagra

medicatielijst apotheek medicijnen zonder recept MedicijnPunt

medicatie apotheek: MedicijnPunt – pseudoephedrine kopen in nederland

normandie pharma: Pharma Confiance – klorane que choisir

https://pharmaconfiance.com/# pure pharma

Medicijn Punt apothekers apotheek zonder recept

Pharma Confiance: Pharma Confiance – pharmacie discount lens

ordonnance pour viagra: my shop cbd – Pharma Confiance

MedicijnPunt Medicijn Punt MedicijnPunt

Medicijn Punt: Medicijn Punt – medicatie online bestellen

viagra tesco pharmacy: finpecia swiss pharmacy – online pharmacy cheap viagra

https://medicijnpunt.shop/# apotgeek

Pharma Connect USA misoprostol pharmacy cost publix pharmacy lipitor

MedicijnPunt: medicijnen zonder recept met ideal – Medicijn Punt

MedicijnPunt: online apotheke – Medicijn Punt

Pharma Jetzt: Pharma Jetzt – PharmaJetzt

Pharma Connect USA adipex diet pills online pharmacy qatar pharmacy cialis

medicaties: Medicijn Punt – MedicijnPunt

apotheken: farma online – MedicijnPunt

http://pharmajetzt.com/# Pharma Jetzt

Pharma Connect USA: ventolin uk pharmacy – Pharma Connect USA

offre pharmacie: fleurs de bach avis consommateur – Pharma Confiance

Pharma Confiance coupe-ongles pieds Г©lectrique Pharma Confiance

Pharma Connect USA: PharmaConnectUSA – clomid online pharmacy

rx care pharmacy pearland tx: top 10 pharmacy websites – order pharmacy online egypt

landelijke apotheek MedicijnPunt MedicijnPunt

http://pharmaconnectusa.com/# rx express pharmacy navarre fl

Pharma Confiance: Pharma Confiance – amoxicilline en vente libre

medicatie apotheek niederlande apotheke MedicijnPunt

apotek online: PharmaJetzt – Pharma Jetzt

Medicijn Punt: MedicijnPunt – Medicijn Punt

medizin bestellen PharmaJetzt PharmaJetzt

http://medicijnpunt.com/# holland apotheke

cialis pharmacy online uk: us pharmacy – fluconazole online pharmacy

Pharma Confiance: achat ozempic – pharmacie et parapharmacie

allergie au carton sildenafil pharmacie prix gff strasbourg

Pharma Jetzt: luitpoldapotheke – nutrim kapseln erfahrungen

heb pharmacy: permethrin online pharmacy – buy concerta online pharmacy

PharmaJetzt medikament kaufen shop spotheke

https://medicijnpunt.shop/# online medicijnen kopen zonder recept

apotheker medicatie: betrouwbare online apotheek – MedicijnPunt

boots pharmacy viagra: pharmacy symbol rx – Malegra FXT plus

Pharma Connect USA diplomat pharmacy Pharma Connect USA

https://pharmajetzt.com/# apotheke bestellen

MedicijnPunt: apohteek – europese apotheek

Pharma Jetzt Pharma Jetzt Pharma Jetzt

https://pharmaconfiance.shop/# mounjaro achat en ligne

Pharma Confiance: Pharma Confiance – Pharma Confiance

Pharma Connect USA: legitimate online pharmacies – Pharma Connect USA

http://medicijnpunt.com/# Medicijn Punt

PharmaConnectUSA Pharma Connect USA costa rica pharmacy online

medicatie bestellen online: Medicijn Punt – MedicijnPunt

MedicijnPunt: Medicijn Punt – medicijn bestellen apotheek

https://pharmaconfiance.com/# paracetamol erection

online apotheek recept: medicatie online – online apotheek zonder recept ervaringen

0nline apotheke: intenet apotheke – Pharma Jetzt

http://pharmajetzt.com/# Pharma Jetzt

internetapotheken apotheke luitpold apotheke

PharmaJetzt: medikamente online bestellen auf rechnung – apotheke online

https://pharmajetzt.com/# Pharma Jetzt

recept online: online apotheken – apotheek winkel 24 review

online apotheek goedkoper: Medicijn Punt – Medicijn Punt

Pharma Connect USA PharmaConnectUSA Pharma Connect USA

Pharma Jetzt: online apotheke pille danach – online apotheke ohne versandkosten

https://pharmaconfiance.shop/# sucer les pieds

https://pharmaconfiance.shop/# pharmagarde 59

Pharma Confiance: Pharma Confiance – huile consacrГ©e

online spotheke: Pharma Jetzt – PharmaJetzt

MedicijnPunt Medicijn Punt mijn medicijnen bestellen

http://pharmaconfiance.com/# pharmacie nhco

xenical mexican pharmacy: PharmaConnectUSA – PharmaConnectUSA

alliance rx specialty pharmacy: PharmaConnectUSA – Pharma Connect USA

PharmaConnectUSA: Pharma Connect USA – Pharma Connect USA

https://pharmajetzt.com/# 123 apotheke

http://medicijnpunt.com/# Medicijn Punt

Prevacid: target pharmacy cialis – rx pharmacy cialis

Pharma Confiance viagra et doliprane test pdg

Pharma Connect USA: diovan pharmacy card – dapoxetine online pharmacy

MedicijnPunt: MedicijnPunt – Medicijn Punt

Pharma Confiance argel 7 en pharmacie avis diffГ©rence entre parapharmacie et pharmacie

Pharma Jetzt: PharmaJetzt – Pharma Jetzt

https://medicijnpunt.com/# Medicijn Punt

envision rx pharmacy: Pharma Connect USA – pharmacy express viagra

https://medicijnpunt.shop/# MedicijnPunt

Pharma Confiance Pharma Confiance Pharma Confiance

apteka den haag: online apotheek recept – Medicijn Punt

https://pharmaconfiance.com/# laboratoire charcot lyon

combien peut on prendre de ketoprofene par jour: distribution de Г fleur de peau – Pharma Confiance

Pharma Connect USA: israel online pharmacy – online pharmacy ventolin inhaler

https://pharmaconfiance.shop/# Pharma Confiance

mediamarkt in meiner nähe PharmaJetzt mediherz shop

https://pharmaconnectusa.com/# online pharmacy college

versandapotheken auf rechnung: PharmaJetzt – Pharma Jetzt

Medicijn Punt: MedicijnPunt – apotheek recept

Pharma Confiance: minceur discount avis – pharmacie europe rouen

versandapotheke deutschland Pharma Jetzt shop apotheke versandkostenfrei

https://pharmajetzt.com/# pillen apotheke

MedicijnPunt: MedicijnPunt – recepta online

Pharma Confiance: amoxicilline et ibuprofГЁne – pharmacie ouverte Г 8h

https://medicijnpunt.shop/# MedicijnPunt

IndiMeds Direct IndiMeds Direct IndiMeds Direct

mexican pharmaceuticals online: TijuanaMeds – TijuanaMeds

canadian discount pharmacy: CanRx Direct – safe canadian pharmacy

canadian online pharmacy best canadian pharmacy to order from canadian pharmacy meds review

http://canrxdirect.com/# best canadian online pharmacy

IndiMeds Direct: IndiMeds Direct – IndiMeds Direct

IndiMeds Direct: IndiMeds Direct – india pharmacy

IndiMeds Direct IndiMeds Direct IndiMeds Direct

canadian drugstore online: CanRx Direct – online canadian pharmacy reviews

pharmacies in canada that ship to the us canada pharmacy online legit canadian pharmacy tampa

http://tijuanameds.com/# п»їbest mexican online pharmacies

online canadian pharmacy: canadian pharmacy world – canadian pharmacy no scripts

reputable mexican pharmacies online medicine in mexico pharmacies TijuanaMeds

reputable mexican pharmacies online: reputable mexican pharmacies online – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

https://canrxdirect.shop/# trustworthy canadian pharmacy

TijuanaMeds: medicine in mexico pharmacies – TijuanaMeds

https://tijuanameds.com/# TijuanaMeds

TijuanaMeds: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – TijuanaMeds

TijuanaMeds: TijuanaMeds – best online pharmacies in mexico

indianpharmacy com best india pharmacy IndiMeds Direct

Online medicine order: top 10 online pharmacy in india – indian pharmacy online

http://canrxdirect.com/# my canadian pharmacy

reputable indian online pharmacy mail order pharmacy india indian pharmacy

https://farmaciaasequible.shop/# Farmacia Asequible

opinion mg: mycostatin sin receta espaГ±a – farmacia sol madrid

ativan online pharmacy: help rx pharmacy discount card – certified online pharmacy viagra

online pharmacy coupons order medicine online viagra in tesco pharmacy

Farmacia Asequible: farmacia dietetica central – Farmacia Asequible

enclomiphene for men: enclomiphene testosterone – enclomiphene for men

http://enclomiphenebestprice.com/# enclomiphene for men

la isla. ml tadalafilo 20 mg comprar farmacia rapida

o reilly pharmacy artane: RxFree Meds – motilium inhouse pharmacy

enclomiphene price: enclomiphene – enclomiphene online

enclomiphene testosterone enclomiphene price enclomiphene for men

RxFree Meds: RxFree Meds – blue cross blue shield online pharmacy

casenlax sobres para que sirve: comprar viagra en murcia – Farmacia Asequible

http://enclomiphenebestprice.com/# enclomiphene citrate

farmacia mas cerca de mi: Farmacia Asequible – comprar ozempic en portugal

RxFree Meds: RxFree Meds – pharmacy rx solutions

enclomiphene buy: enclomiphene for sale – enclomiphene buy

web direct: Farmacia Asequible – epiduo precio farmacia

RxFree Meds viagra verified internet pharmacy practice sites RxFree Meds

https://farmaciaasequible.shop/# ahorro direct

RxFree Meds: RxFree Meds – RxFree Meds

RxFree Meds: spain pharmacy online – pharmacy rx one coupon codes

RxFree Meds reliable online pharmacy cialis RxFree Meds

online pharmacy reviews ambien: creighton university pharmacy online – RxFree Meds

enclomiphene: enclomiphene buy – enclomiphene citrate

enclomiphene enclomiphene best price enclomiphene buy

RxFree Meds: sildenafil citrate pharmacy – online medicine tablets shopping

https://enclomiphenebestprice.com/# enclomiphene citrate

diprogenta niГ±os Farmacia Asequible fumar tramadol

venta de medicamentos por internet: Farmacia Asequible – melhor shopping de barcelona

Farmacia Asequible: recigarum comprar online – melatonina gominolas opiniones

https://farmaciaasequible.shop/# mejor crema despigmentante segГєn la ocu

RxFree Meds: RxFree Meds – buy viagra pharmacy online

Farmacia Asequible: comprar parafarmacia online – lubricante durex opiniones

Farmacia Asequible Farmacia Asequible dodot sensitive 5 plus

Farmacia Asequible: Farmacia Asequible – farmacia la mas barata

RxFree Meds RxFree Meds RxFree Meds

nГєmero de telГ©fono de farmacia: parafarmacia online.com – mi otra farmacia

Farmacia Asequible: Farmacia Asequible – Farmacia Asequible

https://rxfreemeds.shop/# RxFree Meds

tadalafilo 20 mg 8 comprimidos precio farmГ cia i parafarmГ cia droguerГa online barata

enclomiphene best price: enclomiphene online – buy enclomiphene online

Farmacia Asequible: farma higiene opiniones – armacia

comprar loniten 10 mg: brentan crema efectos secundarios – Farmacia Asequible

http://rxfreemeds.com/# RxFree Meds

farmacia online barata y fiable: gripe zaragoza – brentan crema niГ±os

Farmacia Asequible Farmacia Asequible Farmacia Asequible

Farmacia Asequible: farmacian – Farmacia Asequible

RxFree Meds: RxFree Meds – RxFree Meds

tovedeso 3 5 mg Farmacia Asequible casenlax 500 mg/ml

Farmacia Asequible: mejor cepillo dental electrico segun la ocu – comprar heliocare barato

http://farmaciaasequible.com/# Farmacia Asequible

RxFree Meds: RxFree Meds – RxFree Meds

comprar tadalafilo droguerГa cerca Farmacia Asequible

enclomiphene citrate: enclomiphene for sale – enclomiphene online

online pharmacy discount rx logo pharmacy right source pharmacy

enclomiphene for sale: enclomiphene price – enclomiphene for men

Farmacia Asequible: Farmacia Asequible – viagra marca blanca

https://farmaciaasequible.com/# farmacia 24 horas santander

mail order pharmacy india: certified pharmacy online viagra – ritalin online pharmacy reviews

RxFree Meds safeway pharmacy hours people pharmacy zocor

enclomiphene for sale: enclomiphene testosterone – enclomiphene citrate

https://enclomiphenebestprice.com/# enclomiphene online

RxFree Meds united states online pharmacy viagra Lariam

RxFree Meds: RxFree Meds – RxFree Meds

Farmacia Asequible: gelasimi farmacia – Farmacia Asequible

https://farmaciaasequible.com/# iraltone aga plus opiniones

RxFree Meds RxFree Meds RxFree Meds

RxFree Meds: Lamivudin (Cipla Ltd) – RxFree Meds

Farmacia Asequible: farmacia online canarias – farmacia online sin receta

enclomiphene online enclomiphene for men buy enclomiphene online

online pharmacy no prescription ultram: pharmacy drug store near me – RxFree Meds

brentan crema in english: Farmacia Asequible – Farmacia Asequible

Farmacia Asequible Farmacia Asequible farmacis online

https://farmaciaasequible.com/# Farmacia Asequible

RxFree Meds: RxFree Meds – RxFree Meds

https://enclomiphenebestprice.shop/# enclomiphene best price

RxFree Meds RxFree Meds RxFree Meds

Farmacia Asequible: Farmacia Asequible – parafarmacia barata

RxFree Meds: generic viagra online pharmacy reviews – legal online pharmacy cialis

https://rxfreemeds.shop/# online pharmacy delivery delhi

online pharmacy worldwide shipping: RxFree Meds – thai pharmacy online

cbd badajoz farmacia online 24 horas farmaciad

enclomiphene: enclomiphene best price – enclomiphene testosterone

http://farmaciaasequible.com/# Farmacia Asequible

Farmacia Asequible: farmacia + – crema elocom

movicol sin receta Farmacia Asequible de la farmacia

Farmacia Asequible: Farmacia Asequible – emla precio

diprogenta 50 g precio: se puede comprar mycostatin sin receta – Farmacia Asequible

enclomiphene buy enclomiphene for men enclomiphene online

RxFree Meds: RxFree Meds – flagyl pharmacy

MexiMeds Express: buying prescription drugs in mexico online – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs reputable mexican pharmacies online purple pharmacy mexico price list

IndoMeds USA: IndoMeds USA – IndoMeds USA

buying prescription drugs in mexico online: mexican drugstore online – MexiMeds Express

indian pharmacy online top online pharmacy india indianpharmacy com

http://medismartpharmacy.com/# Prandin

MexiMeds Express: MexiMeds Express – MexiMeds Express

accutane northwest pharmacy: MediSmart Pharmacy – overseas pharmacy adipex

IndoMeds USA mail order pharmacy india india pharmacy

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies: MexiMeds Express – buying prescription drugs in mexico

mexican pharmaceuticals online: MexiMeds Express – pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

https://medismartpharmacy.com/# india pharmacy finasteride

online pharmacy buy adipex MediSmart Pharmacy us pharmacy generic viagra

pharmacy rx world canada: MediSmart Pharmacy – best mail order pharmacy canada

pharmacy prices levitra: Zestoretic – mexico pharmacy online

MexiMeds Express MexiMeds Express mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

viagra uk online pharmacy: MediSmart Pharmacy – amoxicillin uk pharmacy

reputable indian pharmacies: india pharmacy mail order – IndoMeds USA

https://indomedsusa.shop/# indian pharmacy

best online pharmacy india IndoMeds USA online shopping pharmacy india

trazodone online pharmacy: MediSmart Pharmacy – online pharmacy australia paypal

canadianpharmacyworld: MediSmart Pharmacy – canadian pharmacy

MexiMeds Express MexiMeds Express MexiMeds Express

tesco pharmacy sildenafil: cytotec malaysia pharmacy – rhinocort online pharmacy

buy prescription drugs from canada cheap: erection pills – best canadian pharmacy to buy from

https://indomedsusa.com/# IndoMeds USA

https://meximedsexpress.com/# MexiMeds Express

п»їbest mexican online pharmacies purple pharmacy mexico price list mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

MexiMeds Express: buying from online mexican pharmacy – MexiMeds Express

canadian pharmacy 365: pharmacy express – is canadian pharmacy legit

MexiMeds Express mexico drug stores pharmacies mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

MexiMeds Express: mexican rx online – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

IndoMeds USA: india pharmacy mail order – IndoMeds USA

https://indomedsusa.shop/# IndoMeds USA

mexico drug stores pharmacies MexiMeds Express MexiMeds Express

mexico pharmacy accutane: MediSmart Pharmacy – fluconazole pharmacy online

canadian world pharmacy: viagra pfizer online pharmacy – canadian pharmacy ed medications

veterinary online pharmacy anabolic steroids online pharmacy reviews unicare pharmacy in artane castle

online pharmacy no prescription required: estrace cream online pharmacy – nizoral boots pharmacy

https://medismartpharmacy.shop/# g and e pharmacy edmonton store hours

price of percocet at pharmacy publix pharmacy cephalexin viagra online pharmacy uk

MexiMeds Express: MexiMeds Express – MexiMeds Express