The case of Sushil Sharma and Naina Sahni is a shocking and sensational incident that left a lasting impact on the criminal justice system. When Sharma discovered his partner, Naina, engaged in a phone conversation with someone of the opposite sex, his response was an extreme fit of rage. This led to a horrifying sequence of events – shooting Naina, dismembering her body, and burning it in a restaurant’s tandoor to destroy evidence.

The gruesome discovery of a burnt and mutilated body in a Delhi restaurant’s tandoor deeply disturbed the nation. This article delves into the details of Sharma’s sudden burst of anger and the subsequent brutal actions, examining the legal complexities that unfolded during court proceedings.

Initially, both the trial court and the Delhi High Court sentenced Sharma to death. However, the case dragged on for almost a decade, prompting the Supreme Court to eventually overturn the judgment and commute it to a life sentence. The article not only explores the chilling facts of the case but also delves into the perplexing mystery of why it took so long to reach a final judgment, discussing various factors that made the resolution of this case particularly challenging.

Essentials of the Case

The brief facts of the case are:

- Sushil Sharma, the ex-president of Delhi Youth Congress, and Naina Sahni, the former General Secretary of the Delhi Youth Congress girls’ wing, both associated with the Delhi Youth Congress, were involved. In 1992, Sushil Sharma purchased a flat in Mandir Marg. The deceased, Naina Sahni, would occasionally visit the flat and is reported to have informally married Sushil Sharma there.

- The accused and deceased’s marriage was kept a secret from the public and was thought to be a covert union. The deceased shared the flat with Sushil Sharma following their marriage. Political figure Sushil Sharma wanted their marriage to remain a secret, but Naina Sahni wasn’t on board. Additionally, he limited his wife’s independence since he had doubts about her character. But Naina Sahni was attempting, with the assistance of a coworker named Matloob Karim, to get away from Sushil Sharma and relocate to Australia. After the couple’s problems escalated for three years, Sushil Sharma arrived at his Mandir Marg flat on July 2, 1995, to discover his wife was deep in conversation with someone on the phone.

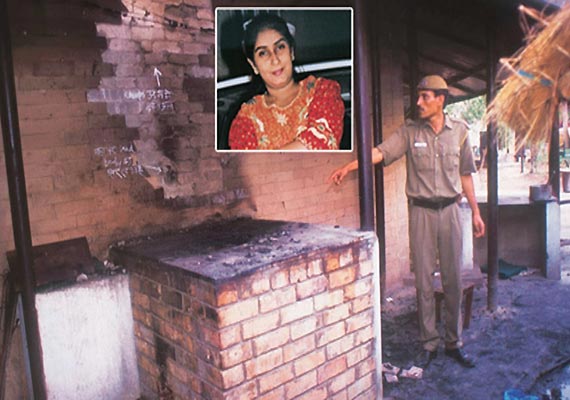

- When Sushil Sharma, his wife’s longtime suspect, checked the number on her phone, he discovered it was Matloob Karim. Sharma pulled out his revolver and fired three shots at Naina after being deeply stunned. Naina had passed away instantly. Following the murder accused Sushil Sharma drove the body to his Bagia Bar-be-que restaurant in his Maruti car. After the body was dismembered, the accused threw it into the tandoor with the assistance of fellow accused Keshav Kumar, a waiter.

- Two police constables noticed that the deceased’s body was burning in the tandoor, and they alerted the control room (100) to the massive amount of flames and smoke coming from the restaurant. When the police arrived at the restaurant to investigate the event, they discovered a woman’s corpse with one of her limbs burned and her guts falling out. Bloodstains on Keshav Kumar’s clothing were discovered by the police and subsequently confiscated. Sushil Sharma, the initial accused, however, left the scene of the crime, travelled to a number of other locations, and on July 10, 1995, he turned himself in in Bangalore.

Which laws apply in this instance?

- Section 34 of IPC: “When a criminal act is done by several persons in furtherance of the common intention of all, each of such persons is liable for that act in the same manner as if it were done by him alone.”

- Section 37 of IPC: “When an offence is committed by means of several acts, whoever intentionally co-operates in the commission of that offence by doing any one of those acts, either singly or jointly with any other person, commits that offence.”

- Section 120-B of IPC: (1) Whoever is a party to a criminal conspiracy to commit an offence punishable with death or rigorous imprisonment for a term of two years or upwards, shall, where no express provision is made in this Code for the punishment of such a conspiracy, be punished in the same manner as if he had abetted such offence.

- Section 201 of IPC: “Causing disappearance of evidence of an offence or giving false information to screen offenders”.

- Section 302 of IPC: “Whoever commits the offence of murder shall be punished with death or imprisonment for life and shall also be liable to fine.”

Legal & statutory issues

- The reason behind the crime was Sharma’s mistrust of his wife’s morality. The case was brought up based on circumstantial evidence (DNA) and a second autopsy, which presented a legal challenge. These were the only grounds utilised to show the accused’s guilt.

- He committed such a horrible crime as a result of the husband and wife’s tense interpersonal relationship, which further provoked him and caused outrage.

- Destruction of murder evidence through conspiracy.

- According to Section 34 of the Indian Penal Code, each individual who commits a crime with the intent of all of them is equally responsible for the act, just as if he had done it alone. Additionally, Sushil Sharma, the accused, and Keshav Kumar, the restaurant employee, both committed crimes intentionally in accordance with Section 37 of the IPC, which states that cooperating in the commission of another person’s crime also counts as a crime.

- The IPC’s Section 120B addresses the penalties for criminal conspiracy. Keshav Kumar’s assistance in burning the body parts in the Tandoor, along with Sharma’s subsequent escape from the crime scene, constitutes his facilitation of the murder and his liability for punishment.

- Keshav Kumar (the co-accused) who helped Sushil disappear from the restaurant and also helped him destroy the corpse was also charged under Section 201 of IPC because he caused the disappearance of evidence with the intention of hiding Sushil from legal action and also he lied about the burning saying it to be old Congress posters, therefore gave an information to the police which was false

- Section 212, which states that harbouring an offender with the intention of shielding him from legal punishment shall be punished as mentioned in the Section, applies to Sushil Sharma’s very easy escape from the restaurant with Keshav Kumar’s help.

- Article 302 of the Indian Penal Code stipulates that a person convicted of murder faces either capital punishment or life imprisonment in prison, in addition to a fine.

OTHER SIMILAR CASES

1. Santosh Kumar Satishbhushan Bariyar vs. State of Maharashtra: – In this Case, the appellant and others were looking for work and had plans to kidnap a friend and demand a ransom later. Rather, they murdered him, dismembered his body, and scattered the fragments around. One of the accused testified against the appellant, leading to the appellant’s execution. The death penalty was upheld by the High Court. The Supreme Court, however, overturned the ruling, stating that there is room for the accused to change their ways and that the procedure for disposing of the dead does not contain the case for the most unusual concept. As a result, the death sentence was reduced to life in prison.

2. Mahendra Nath Dass vs. State of Assam, AIR 1999 SC 1926: – In this Case, the prisoner used a blade to kill the victim, amputate the hand, chop off the head, and transport the decapitated body in a stately manner to the police station. As a result, the Supreme Court ruled that the accused should be executed because the deed was extremely depraved. Even if the current Naina Sahni case demonstrates a highly unethical behaviour, the Honourable Supreme Court decided to reduce Sushil Sharma’s death sentence.

3. Mohd.Chaman State (NCT of Delhi) SC 2000: – The one-year-old daughter in this case suffered injuries from the appellant’s rape, which ultimately resulted in her death. Even though the appellant was given the death penalty by the trial court and the High Court upheld it, the Supreme Court decided that the appellant did not pose a threat to the public and thus overturned the death sentence and converted it to life in prison.

JUDGEMENT

A district court imposed the death penalty on Sharma in 2003. He filed an appeal for the same matter with the Delhi High Court, where he was denied compassion. The court’s 2007 ruling stated:

“People like the appellant who are power drunk and have no value for human life are definitely a menace for the society at large and deserve no mercy. … The act of the appellant is so abhorrent and dastardly that in case death penalty is not awarded to him, it would be a mockery of justice and conscience of the society at large would be shocked. This is surely a case which falls within the category of ‘rarest of rare cases’ in which no other punishment except the death penalty would be justified.”

Subsequently, the 2014 ruling by the Supreme Court states:

“Undoubtedly, the offence is brutal, but the brutality alone would not justify the death sentence in this case.”

To this, the Supreme Court laid down a few criteria on which only if the crime falls will be eligible for awarding the death penalty.

- When the murder is carried out in a way that is incredibly heinous, hideous, demonic, repulsive, or devilish in order to provoke strong and widespread outrage in the community.

- When the motive for the murder shows complete depravity and meanness..

So, the Supreme Court of India has decided that the current case involving a murder in Tandoor and the deliberate and methodical destruction of evidence through chopping and burning is not sufficiently “extremely brutal,… revolting” to incite public anger.

In addition, the death sentence was commuted for additional reasons. Sharma had opportunities for repentance and no “criminal antecedents,” according to the panel. That Sharma’s repeated attempts at domestic cruelty (abuse, restraints, etc.) against Naina Sahni do not qualify as criminal antecedents, meanwhile, is somewhat remarkable. This argument is valid because the domestic assistance provided testimony in court regarding the incidents of abuse.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the Supreme Court’s decision in the current case may be perceived as flawed by some, as it hinges on the distinction that the crime was not against the State but rooted in a strained relationship. However, the brutal nature of the cold-blooded murder, evidenced by attempts to destroy the corpse, reveals a true criminal mindset. While the Sharma murder case may not have been deemed “rarest of the rare,” perhaps societal desensitisation to such crimes influenced this perception. Notably, the appellant was released after 23 years, having served the maximum prescribed sentence, as determined by the Hon’ble Court.

Global expertise that’s palpable with every service.

where to get cheap lisinopril pills

They provide international health solutions at my doorstep.

Namhafte Softwareentwickler bieten ihre Spiele gerne

bei Crocoslots an. Denn bei Crocoslots finden Sie viele,

viele Spiele. Möchten Sie auch ein VIP-Spieler

im Crocoslots Casino werden?

Beim Ersteinzahlungsbonus zum Beispiel müssen Sie mindestens 20 Euro einzahlen. Sie erhalten bis

zu einem Maximum von 1.000 Euro und weitere 50 Freispiele.

Sie erhalten bis zu einem Höchstbetrag von 1.000 Euro und weitere

75 Freispiele. Sie erhalten dann bis zu einem Höchstbetrag von 1.000 € und weitere 100 Freispiele.

Die Website des Casinos ist für mobile Browser optimiert und bietet eine

einfache Navigation, schnelle Ladezeiten und Zugriff auf alle wichtigen Funktionen.

Diese starke Kundensupport-Infrastruktur zeigt das Engagement

von Crocoslots Casino, eine zuverlässige und benutzerfreundliche Erfahrung zu bieten. Die Live-Chat-Option ist

besonders beliebt aufgrund ihrer Schnelligkeit und Bequemlichkeit,

die es Spielern ermöglicht, in Echtzeit Unterstützung bei Themen wie

Spielanfragen, Kontosupport und Bonusfragen zu erhalten. Beim Kundensupport

ist Crocoslots für sein reaktionsschnelles und hilfreiches Serviceteam bekannt.

Crocoslots setzt sich auch für Fairness im Spiel ein und lässt

regelmäßige Audits durch unabhängige Agenturen durchführen,

um die Integrität der Spiele zu wahren und ein vertrauenswürdiges

Spielerlebnis zu gewährleisten.

References:

https://online-spielhallen.de/robocat-casino-auszahlung-ihr-umfassender-leitfaden/

Open the cashier, pick a payment method you trust, and choose an amount that suits your session. Once

your profile is created, you can log in and head to

the account panel. Support chat is available around

the clock and easy to find from both desktop and mobile.

You can deposit and cash out in Australian dollars,

so your balance stays familiar and you dodge the mental maths of constant currency conversion. If you’ve ever had to decode

awkward casino copy at 1 a.m., you’ll appreciate how tidy this feels.

Buttons, game filters, and banking steps read the way you’d expect, so you’re not guessing what a label means mid-session.

Two-factor authentication adds an extra security layer, requiring code verification from your mobile device before

processing withdrawals. Maximum withdrawal limits reach $5,000

per transaction for standard players, scaling up to $10,000+ for VIP members.

E-wallets like Skrill and Neteller provide another instant option for those preferring digital payment platforms.

Bank transfers arrive within 1-3 business days but suit players moving larger amounts.

Customer support stands ready throughout registration via live chat.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/ax99-casino-australian-real-money-gaming-hub/

us poker sites that accept paypal

References:

skillproper.com