Introduction

In the ever-evolving landscape of criminal investigation, forensic science has become an indispensable pillar. One of the most controversial and debated tools under this umbrella is Narco-Analysis. While popularised in media trials and often portrayed as a silver bullet for cracking difficult cases, the legal, ethical, and scientific dimensions surrounding its application raise profound questions. As a tool involving the intravenous administration of psychoactive drugs to obtain information from unwilling subjects, narco-analysis treads a thin line between investigative necessity and fundamental rights violations.

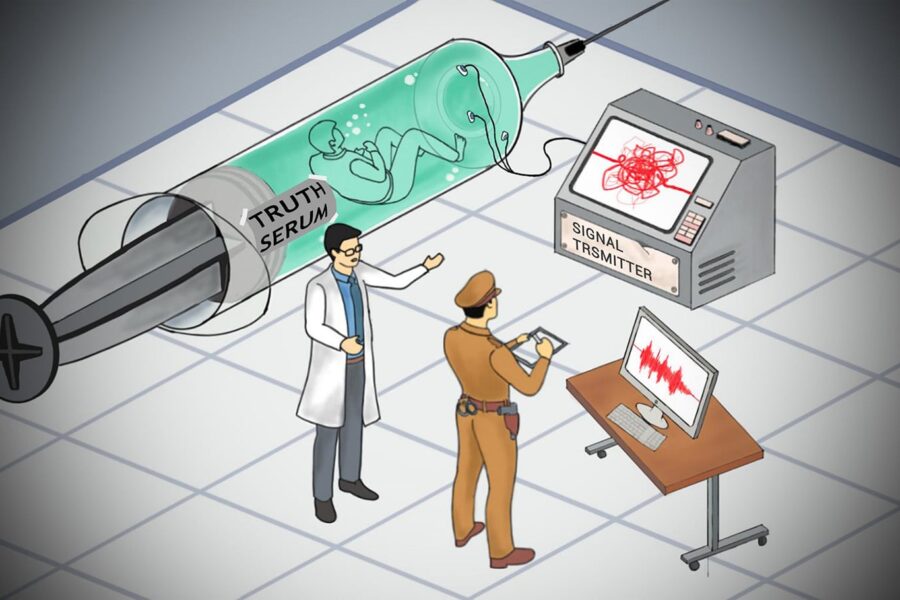

What is Narco-Analysis?

Narco-analysis is a psychotherapeutic technique that uses so-called “truth serums” primarily sodium pentothal or sodium amytal — which are barbiturates that depress the central nervous system and induce a hypnotic or semi-conscious state. In such a condition, it is believed that the subject becomes less inhibited and may divulge information that they may otherwise withhold consciously.

The term ‘narco’ derives from the Greek word narkē, meaning anesthesia or stupor. During a narco-analysis test, a trained anesthesiologist administers the drug, while psychologists or forensic experts question the subject, believing that the inhibition caused by deception is lowered.

Need for Narco-Analysis: Law vs. Truth

The Indian criminal justice system operates on the principles of natural justice, including presumption of innocence, right against self-incrimination, and the adversarial system of trial. However, in complex cases involving terrorism, organized crime, serial killings, or cases with no material evidence, investigating agencies often resort to narco-analysis as a last resort to elicit hidden facts.

The rationale cited includes:

- Absence of direct evidence or eyewitnesses.

- Suspects refusing to cooperate.

- National security exigencies.

- Recovering material objects like weapons or bodies.

However, while the need for effective investigation is critical, such methods bring into sharp conflict constitutional guarantees.

Legal Framework and Constitutional Provisions

In India, no specific statute explicitly authorises narco-analysis. The procedural and constitutional foundation regarding this practice hinges upon two major provisions:

Article 20(3) of the Constitution of India – “No person accused of any offence shall be compelled to be a witness against himself.”

Section 161(2) of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), 1973 – “Every person is bound to answer truthfully all questions put to him by a police officer… except questions the answers to which would have a tendency to expose him to a criminal charge.”

Indian Evidence Act, 1872 – Under Section 25, confessions made to police officers are inadmissible. Moreover, Section 27 allows discovery based on accused’s information only if such information is given voluntarily.

Right to Privacy (Article 21) – As reaffirmed in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017), privacy is a fundamental right and includes bodily and mental integrity.

The Supreme Court Verdict: Selvi v. State of Karnataka (2010)

A landmark judgment that decisively shaped the legal status of narco-analysis in India is Selvi v. State of Karnataka, (2010) 7 SCC 263. In this case, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court dealt with the constitutionality of involuntary administration of narco-analysis, polygraph tests, and brain-mapping.

Key highlights of the judgment:

Involuntary administration violates Article 20(3): The Court ruled that subjecting an accused to narco-analysis without consent is a direct violation of the protection against self-incrimination.

Violation of personal liberty under Article 21: The Court noted that such tests interfere with an individual’s mental faculties, autonomy, and privacy.

Right to fair trial: Involuntary statements obtained during such tests are not admissible as evidence. Any confession must be voluntary, made before a magistrate under Section 164 CrPC.

Consent-based tests may be allowed: However, the judgment left a small window open. If the subject consents to undergo narco-analysis, the test may be permitted under strict supervision, and the results may be used only for further investigation—not as evidence.

Thus, narco-analysis is not outright illegal but severely restricted, requiring explicit informed consent and adherence to procedural safeguards.

Scientific Reliability and Limitations

Contrary to popular belief, narco-analysis is not foolproof. The scientific community remains divided on its reliability for several reasons:

State of semi-consciousness: Under the influence of sodium pentothal, the subject may speak incoherently, mix facts with imagination, or produce false memories.

Suggestibility: The individual becomes highly suggestible and may provide answers that investigators want to hear, rather than the truth.

No guarantee of truth: People under narco influence may still lie or withhold facts due to strong will or mental training.

Lack of standardised methodology: There is no uniform scientific protocol for administering and interpreting narco-analysis results, raising concerns about subjectivity and misuse.

Ethical and Human Rights Concerns

The use of narco-analysis raises numerous ethical dilemmas:

Informed consent: Whether consent is genuinely voluntary in custodial environments is debatable.

Bodily autonomy: Forced medical procedures for investigation undermine the dignity of the individual.

Potential for torture: In many instances, narco-analysis is used alongside custodial interrogation, raising fears of coercion and abuse.

Public perception and media trials: Leaked narco-analysis tapes have often prejudiced public opinion, violating the principle of presumption of innocence.

International human rights standards, such as the UN Convention Against Torture, to which India is a signatory (though not ratified), prohibit degrading treatment or forceful extraction of information.

Judicial Use and Evidentiary Value

Even when conducted with consent, the results of narco-analysis are not admissible in court as substantive evidence. However, the revelations during the test can lead to:

Discovery of physical evidence (Section 27 of Evidence Act).

Identifying accomplices.

Verifying timelines or investigating leads.

The evidentiary value lies in the derivative use, not in the content of the statements made during the test. The court relies on corroborative evidence, not the test result itself.

Narco-Analysis in High-Profile Cases

Despite legal restrictions, narco-analysis has featured prominently in several high-profile investigations:

Nithari Killings (2006) – The accused Surinder Koli and Moninder Singh Pandher were subjected to narco tests, revealing gruesome details.

Arushi Talwar Murder Case (2008) – Narco-tests of domestic servants became a controversial part of the probe.

Abu Salem (Mumbai blasts), Telgi scam, and Godhra train burning case also saw reliance on such techniques, though with varied success.

These cases underscore the increasing dependence on forensic psychology in cases where physical evidence is lacking, and the balance between investigative utility and individual rights is severely tested.

Comparative International Perspective

United States: Narco-analysis is largely inadmissible and disfavored. The 1963 Townsend v. Sain case declared confessions under drug influence as coerced.

United Kingdom: Such tests are almost never used; any confession made under drug influence is deemed unreliable.

Russia and some Latin American countries reportedly continue to use truth serums under specific legal frameworks, though often criticized by human rights bodies.

India’s legal system, therefore, follows a cautious middle path, recognizing the investigative need but not allowing its abuse.

Conclusion: Where Should the Law Stand?

To move forward, a clear legislative framework, guided by ethical and scientific standards, is necessary. Any future use of narco-analysis must be:

Based on informed consent;

- Conducted under judicial supervision;

- Limited to investigative aid;

- And strictly excluded from being used as direct evidence in court.

As India modernizes its forensic capacities, the temptation to rely on such techniques must be balanced by an unyielding commitment to due process, human dignity, and rule of law. In the end, no tool, however efficient, should compromise the foundational principles of justice.

Contributed By Paridhi Bansal (Intern)