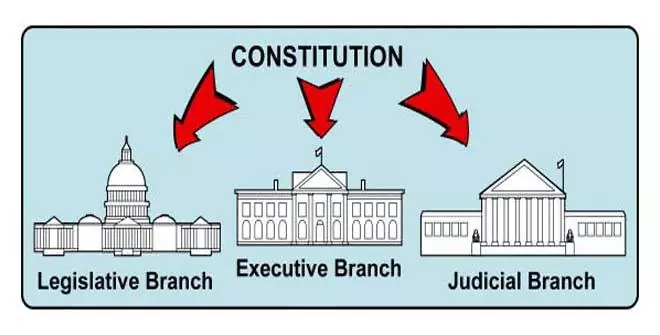

The political theories of Locke and Montesquieu are where the idea of separation of powers first emerged. “There can be no liberty where the legislative and executive powers are united in one person, or body of magistrates,” as Montesquieu observes in The Spirit of Laws (1748). This fundamental concept gave rise to the theory of separation of powers, which maintains the functional independence of the three main state institutions: the legislative, executive, and judicial branches.

Meaning

Various scholars define the separation of powers in different ways. However, three general characteristics define what separation of powers means:

- An individual who is a part of one organ shouldn’t be a part of another.

- The operation of one organ should not impede the operation of the others.

- An organ should never perform a duty that belongs to another organ.

The idea of Trias Politica serves as the foundation for the division of powers. This idea illustrates a tripartite structure in which three organs, each with a defined authority, are each given a delegation of powers.

Foundation of the Doctrine

Two fundamental tenets form the basis of Montesquieu’s theory:

- Governmental powers must be divided and balanced across several institutions in order to prevent arbitrary rule and protect individual liberty.

The core of this theory, according to the Supreme Court in State of West Bengal v. Committee for Protection of Democratic Rights (2010), is having checks and balances to shield people from potential abuses by any one institution.

- Every branch of the government must be restricted to carrying out its designated duties and not be permitted to interfere with the operations of other branches.

As stated in Ram Jawaya v. State of Punjab (1955), the Indian Constitution delineates the powers in a way that facilitates seamless governance, rather than adhering to a strict division of powers. However, one organ’s encroachment on the domain of another is forbidden.

The Three Rules of Distancing

Montesquieu divided separation into three categories:

- It is not appropriate for one organ to impede the function of another. This encourages efficiency and specialisation in governance.

- An organ cannot perform duties assigned to another. The Supreme Court ruled in Government of A.P. v. P. Laxmi Devi (2008) that neither the legislative nor the executive branch may perform judicial powers.

- It is not appropriate for one person to be a part of multiple organs. Conflicts of interest and power abuse are avoided as a result.

Constitutional status of separation of power in India

After reading the Indian Constitution’s contents, one could conclude that it is accepted throughout India. As per the Constitution of India:

| Legislature | Parliament ( Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha)State legislative bodies |

| Executive | At the central level- PresidentAt the state level- Governor |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court, High Court and all other subordinate courts |

There are no limitations on the Parliament’s ability to enact laws; it is fully capable of doing so, provided that it complies with the Constitution’s requirements. Articles 62 to 72 of the Constitution itself specify the president’s authority and duties. The judiciary is independent in its domain and is not hindered in its judicial duties by the legislative or executive branches. The court has the authority to declare any law approved by the legislature unconstitutional if it conflicts with the Fundamental Rights (Article 13). The High Court is granted this power via Articles 226 and 227 of the Constitution, and the Supreme Court is given this power under Articles 32 and 136. After reviewing these clauses, several jurists believe that the doctrine of separation of powers is accepted in India.

Advantages of the Theory

- Among the advantages Montesquieu saw in function separation were:

- preventing despotism and defending personal liberty

- encouraging job specialisation across institutions

- ensuring responsibility as a means of mutual verification

- Increasing governance’s effectiveness

In Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973), the Supreme Court stated that this theory guards against “unfettered social control” by any one organisation.

Adjustments for Useful Governance

Although the fundamental ideas are sound, various adjustments are needed in actual use:

The legislature selects the members of the Council of Ministers, breaking the prohibition against holding office in more than one body. The Indian Constitution establishes a “blurred separation of powers,” as noted by Granville Austin.

The Parliament is where the executive is answerable and where its actions can be contested.

The executive can act in limited ways through delegated legislation. Similar to this, the executive uses judicial knowledge on specialised topics when performing quasi-judicial duties.

In re Delhi Laws Act (1951), the Supreme Court ruled that administrative “necessities and convenience” justify the permission of certain overlap in functions. Complete separation is neither possible nor prudent. A harmony between the organs allows a “community of action” for effective governance.

Overlapping powers of the Legislature

With the Judiciary

- Impeachment and dismissal of judges

- Authority to revalidate legislation that the Court had deemed ultra vires and amend them.

- If its privilege is violated, it has the authority to penalise the offending party.

With the Executive

- Members of the legislature serve as the leaders of each governmental ministry.

- It can dissolve the government with a vote of no confidence.

- The ability to evaluate the executive’s job.

- President’s impeachment.

- Members of the legislature are chosen to the council of ministers, on whose advice the President and Governor act.

Overlapping powers of the Executive

With the Judiciary

- choosing applicants for the Chief Justiceship and other legal roles.

- the power to reduce penalties, pardons, reprieves, or respites for criminal defendants.

- Judicial duties are also performed by the executive tribunals and other quasi-judicial entities.

With the Legislative

- the power to pass an ordinance with the same legal force as a bill approved by the legislative branch of a state or the parliament.

- They are able to create regulations that control their specific procedures and commercial practices, within the bounds of this Constitution.

- A delegated law bestows powers.

Overlapping powers of the judiciary

With the Legislative

- In order to guarantee complete justice, the Supreme Court functions as an Executive under Article 142.

With the Executive

- Legal review is the power to investigate executive actions to determine whether or not they violate the Constitution.

- The Constitution’s fundamental framework cannot be altered.

Conclusion

The balance between the three parts of government is crucial to maintaining liberty, but growing concerns for security and welfare have led to an expansion in the executive’s power. In an ideal society, each individual’s liberty, well-being, and the safety of the state should all be given equal weight. Without a doubt, this would call for a powerful government, but it would also call for the separation of powers and a system of checks and balances.

To sum up, Montesquieu’s theory is still very relevant today since it establishes a moral framework for effective and responsible government. Pragmatic adjustments, on the other hand, allow for positive overlap in situations where rigidly divided functions might impair coordinated organ functioning. A fair division of powers is included in our Constitution to protect liberty and promote effective government.

Adv. Khanak Sharma

wohh precisely what I was searching for, appreciate it for putting up.