In a democratic society like India, the media serves as a vital pillar, often termed the “fourth estate.” It plays a crucial role in disseminating information, shaping public opinion, and holding those in power accountable. However, in recent years, the phenomenon of “media trials” has raised serious concerns about its interference with the administration of justice and the fundamental right to a fair trial. The balance between freedom of the press and the right to a fair trial under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution is at the core of this debate.

This article critically analyses the concept of media trials, the constitutional provisions involved, significant judicial pronouncements, and the need for regulation to preserve the sanctity of the judicial process.

Understanding Media Trials

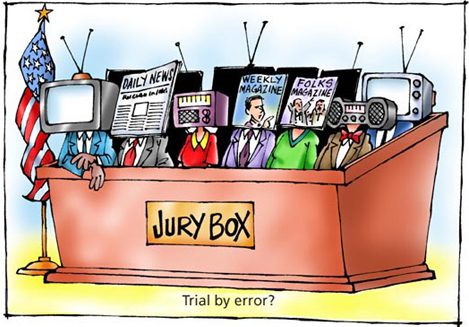

Media trials refer to the intense media coverage and commentary surrounding criminal cases, especially those involving celebrities, politicians, or high-profile individuals. The media, in its quest for sensationalism and higher viewership, often conducts parallel investigations, interviews witnesses, and presents accused persons as guilty even before the court of law pronounces a verdict.

Such reporting can influence public perception, prejudice potential jurors or judges, and undermine the accused’s right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty. The situation becomes even more alarming when the line between investigative journalism and sensationalism is blurred.

Constitutional Provisions Involved

1. Article 19(1)(a)—Freedom of Speech and Expression:

The Indian Constitution guarantees the freedom of speech and expression to all citizens, which includes the freedom of the press. This right empowers the media to investigate, report, and comment on public issues, including ongoing legal proceedings.

2. Article 21 – Right to Life and Personal Liberty:

This article enshrines the right to a fair trial as an essential part of the right to life. The Supreme Court of India has held in several cases that a fair trial is a fundamental right of every accused.

3. Article 129 and 215 – Powers of Supreme Court and High Courts to Punish for Contempt:

These articles confer upon the higher judiciary the authority to punish for contempt of court, which includes any act that interferes with or obstructs the administration of justice, such as prejudicial media reporting.

Judicial Pronouncements

The Indian judiciary has often expressed concern over the prejudicial impact of media trials. Some landmark cases include:

1. R.K. Anand v. Registrar, Delhi High Court (2009):

In this case, the Supreme Court criticised the media for conducting a parallel trial in the BMW hit-and-run case. The Court emphasised that the media must exercise restraint and ensure that their reportage does not prejudice ongoing judicial proceedings.

2. Sahara India Real Estate Corp. Ltd. v. SEBI (2012):

The court introduced the concept of “postponement orders” to balance freedom of expression and the right to a fair trial. It held that courts can temporarily restrain media reporting if it threatens to prejudice the trial.

3. State of Maharashtra v. Rajendra Jawanmal Gandhi (1997):

The court observed that trial by media is antithetical to the rule of law and can lead to a miscarriage of justice. It reiterated that only a court of law is competent to decide on guilt or innocence.

Media Ethics and Responsibility

Media houses are expected to follow ethical journalism standards, such as verifying facts, avoiding sensationalism, and respecting the privacy and dignity of individuals. The Press Council of India (PCI) issues guidelines to ensure responsible reporting. However, PCI’s recommendations are advisory in nature and lack enforcement power, leading to frequent violations.

Trial by media is often fueled by competition for TRPs, social media virality, and lack of stringent regulation. This not only jeopardises the accused’s right to a fair trial but also affects the integrity of witnesses and public trust in the justice system.

Comparative Jurisprudence

In the United States, the First Amendment protects freedom of the press, but courts impose “gag orders” to restrict media reporting in high-profile cases. Similarly, the UK follows the Contempt of Court Act, 1981, which prohibits publications that could prejudice ongoing trials.

India lacks such comprehensive statutory regulations to deal with prejudicial reporting, relying primarily on contempt powers and self-regulatory mechanisms.

Need for Regulation

There is an urgent need to establish clear legal provisions that strike a balance between media freedom and the right to a fair trial. Suggestions include:

1. Statutory code of conduct for media during sub judice matters.

2. Empowering the PCI or creating an independent media regulatory authority.

3. Greater judicial willingness to issue postponement orders or restrain prejudicial coverage.

4. Awareness and training programs for journalists on legal and ethical reporting.

Conclusion

While the media plays an indispensable role in a democracy, it must exercise its freedom with responsibility, especially when it concerns ongoing judicial proceedings. The right to a fair trial is not only a constitutional mandate but also a cornerstone of justice. Media trials, if left unchecked, can erode this right and distort the judicial process. It is imperative for the legislature, judiciary, and media bodies to work together to ensure that justice is not only done but is seen to be done, free from media pressures and prejudices.

Contributed by: Vanshika Dhiman (Intern)