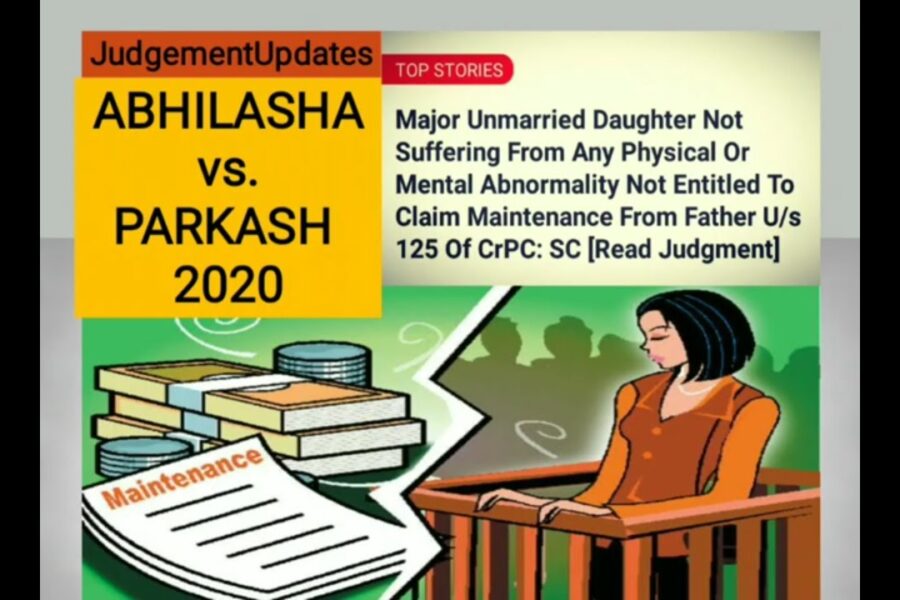

Abhilasha v/s Prakash

A woman filed an appeal in the matter of Abhilasha v. Prakash against the High Court’s ruling against her husband over support awarded to her and her three children—two sons and a daughter—under section 125 of the CrPc. Abhilasha, her youngest daughter, is the appellant in this case.

Although her daughter’s claim for maintenance was granted because she was a minor and only qualified for maintenance upon reaching majority in accordance with section 125 CrPC, her mother’s application for maintenance was denied by the Judicial Magistrate for her two children.

The four applicants then moved to the session court which stated that the appellant i.e., Abhilasha is entitled to maintenance only up to the time when she attains majority and not after that. Then she moved to the High Court where her application was rejected. She filed an appeal with the Supreme Court which was dismissed.

BRIEF OF THE CASE:

An appeal was filed against the High Court’s decision. A woman submitted an application under section 125 Cr.P.C., seeking maintenance for herself and her three children from her husband. The Judicial Magistrate in Rewari rejected the appeal for two children, but approved the maintenance application for the third child, Abhilasha, who was a minor at that time. The Judicial Magistrate granted maintenance to Abhilasha until she reaches adulthood under section 125 of Cr.P.C.

All four applicants filed a criminal revision application in the session court, which was dismissed on February 17, 2011. The Learned Additional Sessions Judge determined that, according to Section 125 Cr.P.C., adult children are eligible for maintenance if they are unable to support themselves due to physical or mental issues. It was concluded that the fourth applicant (appellant, Abhilasha) did not have any such abnormalities or injuries, so she was granted maintenance only until April 26, 2005, the date she reached adulthood. Dissatisfied with both the Sessions Judge’s and Judicial Magistrate’s decisions, an application under Section 482 Cr.P.C. was filed in the High Court by all the applicants, including the appellant.

Then an appeal was filed to High Court against the judgement of the Additional Sessions Judge which was rejected on February 16, 2018, by the High Court. Then they filed an appeal to the Supreme Court.

ISSUES:

- Is the adult, unmarried appellant eligible for maintenance from the respondent under Section 125 of the CrPC, even though she doesn’t have any physical or mental issues?

- Can the decisions of the Judicial Magistrate and Additional Sessions Court, which restricted the appellant’s right to seek maintenance until she reaches adulthood (April 26, 2005), be overturned, thereby holding the respondent responsible for providing maintenance to his daughter even after she turns 18 and remains unmarried?

PROVISIONS:

Code Of Criminal Procedure, 1973

Section 125 – Order of Maintenance of Wives, Children and Parents.

- If any person having sufficient means neglects or refuses to maintain:

- his wife, unable to maintain herself, or

- his legitimate or illegitimate minor child, whether married or not, unable to maintain itself, or

- his legitimate or illegitimate child (not being a married daughter) who has attained majority, where such child is, by reason of any physical or mental abnormality or injury unable to maintain itself, or

- his father or mother, unable to maintain himself or herself, a Magistrate of the first class may, upon proof of such neglect or refusal, order such person to make a monthly allowance for the maintenance of his wife or such child, father or mother, at such monthly rate not exceeding five hundred rupees in the whole, as such Magistrate thinks fit, and to pay the same to such person as the Magistrate may from time to time direct:

Provided that the Magistrate may order the father of a minor female child referred to in clause (b) to make such allowance, until she attains her majority, if the Magistrate is satisfied that the husband of such minor female child, if married, is not possessed of sufficient means.

Explanation: For the purposes of this Chapter:- “minor” means a person who, under the provisions of the Indian Majority Act, 1875 (9 of 1875); is deemed not to have attained his majority;

- “wife” includes a woman who has been divorced by, or has obtained a divorce from, her husband and has not remarried.

The Hindu Adoption And Maintenance Act, 1956

Section 20 – Maintenance of Children and Aged Parents

This section states that:

Subject to the provisions of this section a Hindu is bound, during his or her lifetime, to maintain his or her legitimate or illegitimate children and his or her aged or infirm parents.

A legitimate or illegitimate child may claim maintenance from his or her father or mother so long as the child is a minor.

The obligation of a person to maintain his or her aged or infirm parent or a daughter who is unmarried extends in so far as the parent or the unmarried daughter, as the case may be, is unable to maintain himself or herself out of his or her own earnings or other property.

JUDGEMENT

The Supreme Court stated that an unmarried Hindu daughter is eligible for maintenance from her father until marriage under Section 20(3) of the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956. However, to claim maintenance, she must prove her inability to support herself.

To enforce these rights, she should file an application under Section 20 of the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act. In this case, as the application was filed under Section 125 of the CrPC instead of Section 20 of the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, it was deemed not maintainable. Under Section 125 CrPC, only adult children facing challenges due to physical or mental issues are entitled to maintenance, which wasn’t the situation for the appellant.

The Supreme Court emphasized the differences between Section 20 of the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act and Section 125 of the CrPC. Section 125 CrPC provides immediate relief in a summary proceeding, while Section 20 of the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act offers broader rights determined by a Civil Court.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the Supreme Court made a fair decision by affirming that, under Section 20 of the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956, an unmarried daughter who has reached adulthood has the right to seek maintenance from her father if she cannot support herself and relies on others.

Despite the initial rejection by the Magistrate, the Supreme Court noted that the magistrate court had awarded interim maintenance in line with Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. The application was ultimately granted, reinforcing that an unmarried daughter’s claim for maintenance from her father, especially when she is unable to maintain herself, is a right granted by personal law and can be legally enforced.

The Supreme Court, basing its decision on Section 20 of the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, highlighted the legal obligation of a Hindu to support aging parents and unmarried children who cannot maintain themselves. The Court clarified that an unmarried daughter, having attained majority and lacking any severe physical or mental issues, is not entitled to claim maintenance under the CrPC. Emphasizing the swift relief objective of this section, the court dismissed the application but granted the appellant the option to pursue maintenance under Section 20 of the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956, reinforcing the legal commitment for the father to provide support in such circumstances.

A trusted name in international pharmacy circles.

buy lisinopril for sale

A trailblazer in international pharmacy practices.

A pharmacy that breaks down international barriers.

can i order cheap cipro without insurance

I value their commitment to customer health.

Their online prescription system is so efficient.

order cipro for sale

Always greeted with warmth and professionalism.

From greeting to checkout, always a pleasant experience.

get generic lisinopril without prescription

Their health seminars are always enlightening.

I value their commitment to customer health.

can prozac and gabapentin be taken together

Their international health advisories are invaluable.

Outstanding service, no matter where you’re located.

how to get clomid without prescription

A global name with a reputation for excellence.