What is House Arrest?

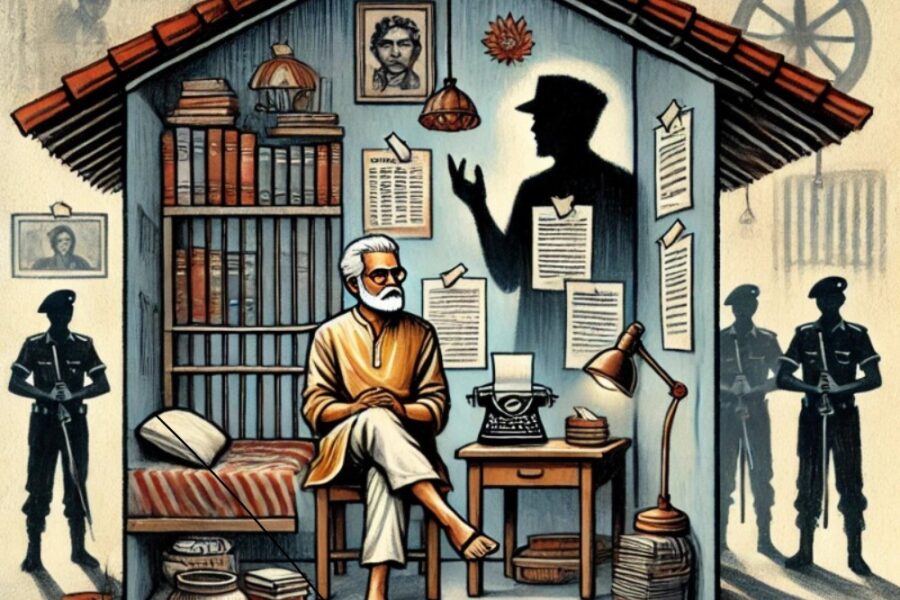

House arrest in India is a form of detention in which individuals are confined to their residence under strict monitoring, usually by law enforcement authorities. This form of restriction can be employed under laws like the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) or the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) when the individual is deemed a security risk but not an immediate threat requiring incarceration in a prison. While house arrest can serve as an alternative to custodial detention, it is often controversial because it limits the individual’s freedom without full access to judicial redress.

Gautam Navlakha, a journalist, civil rights activist, and intellectual, has been a controversial figure in India for decades. His name became prominent in discussions surrounding the term “Urban Naxals,” a label used to describe individuals accused of supporting or sympathizing with the outlawed Communist Party of India (Maoist). The Urban Naxal movement has been portrayed as an ideological and logistical support system for the rural Maoist insurgency, often challenging the Indian state through intellectual discourse, civil society activities, and alleged covert operations.

Background of Gautam Navlakha

Gautam Navlakha’s career spans journalism, human rights advocacy, and political activism. He has been a member of the People’s Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR), an organization that investigates and reports on human rights violations in India. His work has focused on issues such as custodial torture, extrajudicial killings, and the plight of marginalized communities.

Navlakha’s ideological leanings have often aligned with leftist thought, emphasizing state accountability and critiquing authoritarian tendencies. While his supporters hail him as a staunch defender of civil liberties, critics argue that his writings and activities indirectly validate or support extremist movements, including Maoist insurgencies.

Why was Gautam Navlakha placed under house arrest?

In Gautam Navlakha’s case, house arrest was implemented as part of his detention under the UAPA in connection with the Bhima Koregaon violence and alleged Maoist links. Navlakha contested his prolonged detention, including his appeal to have house arrest conditions eased and his eventual move to judicial custody. His case highlights the legal ambiguities and human rights concerns surrounding house arrest. Critics argue that such detentions, especially without a timely trial, undermine due process and risk becoming punitive measures rather than precautionary actions. The Supreme Court of India has stressed that house arrest should be applied judiciously, with its duration and conditions subject to regular judicial review. While the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) does not explicitly contain a provision for “house arrest” as a form of detention, house arrest is typically a judicially directed measure and not a standalone detention category under the UAPA.

Courts in India may impose house arrest as a condition under broader powers of custody while addressing pre-trial detention or ongoing investigations. This decision is often based on the interpretation of judicial powers and custodial requirements under Section 167 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), which governs the procedure for the detention of accused persons during an investigation.

In cases under the UAPA, courts may decide to allow house arrest as an alternative to incarceration, particularly in situations involving humanitarian concerns, such as the age or health of the accused, as seen in Gautam Navlakha’s case. The Supreme Court ruled in November 2021 that Navlakha could serve his detention under house arrest, citing his deteriorating health and advanced age. However, this was framed within the judiciary’s discretion and not as a statutory requirement under the UAPA itself.

The Urban Naxal Phenomenon

The term “Urban Naxal” gained traction with filmmaker Vivek Agnihotri’s book Urban Naxals: The Making of Buddha in a Traffic Jam. The term broadly refers to intellectuals, activists, and scholars allegedly working to further the Maoist agenda in India’s urban centres. Unlike rural Maoists, who are armed insurgents operating in forested regions, Urban Naxals are accused of functioning as ideological enablers, providing financial, logistical, and strategic support.

Critics of the term argue that it has been weaponized to discredit dissent and stifle critical voices. They contend that labelling individuals as Urban Naxals without substantial evidence undermines democratic freedoms and fosters a climate of fear.

Gautam Navlakha’s Alleged Role

Navlakha’s association with the Urban Naxal narrative came to the forefront after his arrest in August 2018 in connection with the Elgar Parishad case. The case involved allegations that activists and intellectuals had incited violence at Bhima Koregaon, a village in Maharashtra, during the bicentenary celebrations of the Battle of Bhima Koregaon.

According to the National Investigation Agency (NIA), Navlakha and others accused in the case were part of a larger conspiracy to destabilize the Indian state. Evidence cited by the NIA included purported correspondence between Navlakha and CPI (Maoist) operatives, references to procurement of arms, and alleged involvement in mobilizing resources for the Maoist movement.

Navlakha and his legal team have consistently denied these allegations, calling them fabricated and politically motivated. His defense has argued that his work as a journalist and human rights advocate involved engaging with various perspectives, including those of insurgent groups, to understand and report on conflict zones.

Civil Society and Human Rights Concerns

The case against Gautam Navlakha has sparked widespread debate about the line between activism and sedition. Supporters argue that targeting intellectuals like Navlakha erodes democratic values and creates a chilling effect on civil society. Organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have criticized the Indian government’s approach, suggesting it is part of a broader crackdown on dissent.

The use of stringent laws like the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) in cases like Navlakha’s has also been a point of contention. Critics argue that such laws allow for prolonged detention without trial, undermining the principle of “innocent until proven guilty.” In Navlakha’s case, he has spent years in custody, with bail being repeatedly denied, raising concerns about the misuse of legal frameworks to suppress dissent.

Appeals in Navlakha’s Case

Gautam Navlakha appealed his detention at multiple levels, focusing on the legality of his arrest, the conditions of his custody, and the charges under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). Initially arrested in August 2018 in connection with the Bhima Koregaon case, he contested his detention in various courts, arguing that it was unlawful and politically motivated.

Key Stages of Appeal:

- Challenging the Initial Arrest: Navlakha appealed to the Delhi High Court, which quashed his transit remand in October 2018, effectively invalidating his arrest. However, the Supreme Court reinstated the charges, allowing the investigation to proceed.

- Request for Bail and Relief: Navlakha applied for regular bail, citing the lack of concrete evidence and his deteriorating health. These appeals were repeatedly denied by the trial court and higher courts, citing the severity of charges under the UAPA.

- House Arrest Appeal: In 2021, the Supreme Court allowed Navlakha to be placed under house arrest instead of jail detention due to his advanced age and poor health. This decision was considered significant as it acknowledged humanitarian concerns while ensuring his availability for investigation.

- Challenging Prolonged Detention: Navlakha also argued that his prolonged detention violated his fundamental rights under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, which guarantees the right to life and liberty. His legal team contended that the prosecution lacked substantive evidence to justify his continued detention.

The Urban Naxal Debate: Diverging Perspectives

Proponents of the Urban Naxal Narrative

Supporters of the Urban Naxal narrative believe that individuals like Navlakha play a critical role in sustaining the Maoist insurgency. They argue that:

- Urban intellectuals provide ideological validation to the movement, glorifying Maoist objectives while downplaying the violence inflicted by insurgents.

- These individuals allegedly act as conduits for urban resources, including funding, arms, and recruits.

- The movement’s survival depends on a symbiotic relationship between rural guerrillas and urban enablers.

Critics of the Narrative

Critics, however, dismiss the Urban Naxal framework as a political tool to delegitimize dissent. They contend that:

- The narrative conflates legitimate dissent with sedition, threatening free speech and the right to critique government policies.

- Evidence in cases like Navlakha’s often relies on questionable sources, such as tampered digital files or coerced testimonies.

- The focus on Urban Naxals detracts from addressing structural issues, such as inequality and marginalization, which fuel insurgencies in the first place.

The Broader Implications

The Gautam Navlakha case highlights tensions between national security and civil liberties in India. While the state argues that it must act decisively against forces threatening its sovereignty, critics warn against the erosion of democratic principles.

For Activists and Journalists

The targeting of individuals like Navlakha raises concerns about the shrinking space for activism and journalism. Investigative reporting on sensitive issues, such as insurgencies or state abuses, may now carry the risk of legal repercussions.

For Democracy and the Rule of Law

The use of broad anti-terror laws like the UAPA underscores the need for judicial oversight and accountability. Without safeguards, there is a risk that such laws may be misused to silence dissent rather than address genuine security threats.

For Counterinsurgency Strategies

The focus on Urban Naxals may divert attention from addressing the root causes of the Maoist insurgency, including land rights, displacement, and social injustice. A holistic approach to counterinsurgency would involve addressing these grievances alongside security measures.

Conclusion

Gautam Navlakha’s case embodies the complexities of balancing national security with the protection of civil liberties in a democratic society. While the state’s concerns about Maoist insurgencies and their urban networks are valid, it is equally critical to ensure that these concerns do not justify the suppression of dissent or the erosion of democratic freedoms.

The Urban Naxal narrative, with its polarizing implications, calls for a nuanced understanding that distinguishes between genuine threats and the exercise of fundamental rights. For India to remain a robust democracy, it must uphold the principle that dissent, even when uncomfortable, is not a crime but a cornerstone of its identity.

Contributed by: Dev Kaan Sindwani(Intern)