Introduction

The right to free speech is the beating heart of any democracy. It safeguards dissent, enables dialogue, and acts as a check on state power. In India, this right is constitutionally enshrined in Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution, guaranteeing citizens the freedom of speech and expression. However, this freedom is not without limits. Article 19(2) authorizes the State to impose “reasonable restrictions” in the interests of public order, decency, morality, and most critically, to curb speech that incites hatred.

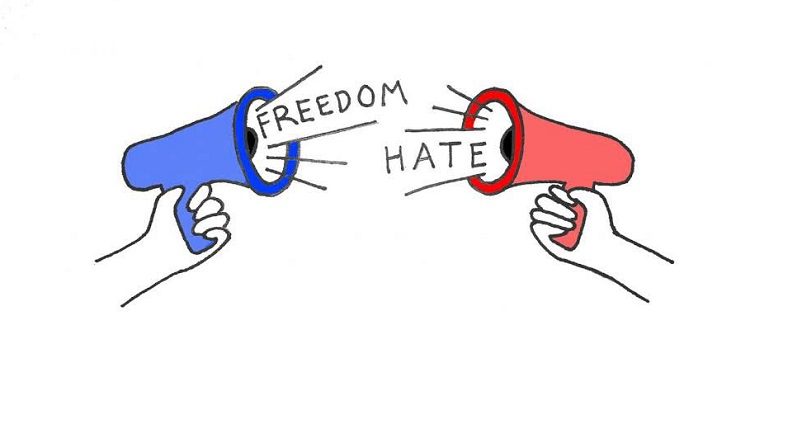

In an era where online platforms amplify every voice and where identity politics fuel sharp divisions, distinguishing between protected free expression and hate-fueled rhetoric is a legal and moral imperative. The challenge lies not in identifying overt hate, but in resolving the grey zones when speech offends, critiques, agitates, or provokes without necessarily crossing into criminality. Where must we draw the line and who should draw it?

The Architecture of Free Speech in India

Freedom of speech in India extends to spoken and written words, symbolic acts, artistic expression, and press freedom. Its essential function is to empower individuals to:

- Participate meaningfully in democracy.

- Criticize public authorities and societal norms.

- Challenge orthodoxy in religion, politics, or culture.

The Supreme Court of India has, in multiple rulings, emphasized that this right includes the freedom to disagree even aggressively. In Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras (1950), the Court called free speech the foundation of democratic governance. But this foundation, as the framers understood, needed reinforcement against irresponsible speech that can threaten the nation’s pluralistic fabric.

Defining Hate Speech: Beyond Offense

India lacks a single, comprehensive definition of hate speech. The Law Commission of India (267th Report, 2017) defined it as speech that:

- Attacks individual or group identity based on religion, caste, race, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation.

- Incites discrimination, hostility, or violence.

- Degrades social harmony.

What differentiates hate speech from offensive speech is not the discomfort it causes, but its potential to dehumanize, radicalize, or incite aggression. Mere criticism of a religion or ideology, even if provocative, is often protected. But calling for extermination, exclusion, or subjugation of a group goes beyond constitutional boundaries.

Though India lacks a specific “hate speech law”, it has several provisions across statutes to regulate incitement:

India’s Legal Tools Against Hate Speech

1. Indian Penal Code (IPC):

- Section 153A: Criminalizes promotion of enmity between groups based on religion, caste, or race.

- Section 295A: Punishes deliberate acts intended to outrage religious feelings.

- Section 505(1)(b): Penalizes statements causing alarm or inciting others to commit offenses.

2. Representation of the People Act, 1951:

- Disqualifies candidates who promote enmity in election campaigns.

3. Information Technology Act, 2000:

- Though Section 66A was struck down (Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, 2015), platforms remain liable under intermediary guidelines for not removing hate content.

Judicial Position: Drawing the Constitutional Boundary

Indian courts have often leaned toward protecting robust debate, unless it crosses into incitement:

- Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015): Distinguished between discussion, advocacy, and incitement. Only the last, which poses a real threat to public order, can be restricted.

- Subramanian Swamy v. Union of India (2016): Held that truth spoken for the public good, even if offensive, cannot be criminalized.

- Ameeq Jameel v. Union of India (2019): The Madras High Court warned against vague bans on “hurt sentiments,” emphasizing the need to protect even unpopular speech.

The courts have insisted that the “chilling effect” of vague laws can silence valuable discourse. But they also recognize that unchecked hate speech, especially by political leaders, can normalize bigotry and instigate communal riots.

Challenges in Regulation: The Tension Points

1. Politicization of Hate Speech

The biggest barrier to consistent enforcement is selective prosecution. Political and religious leaders who incite hatred often escape punishment due to their influence, while ordinary citizens are disproportionately targeted for minor offenses.

2. Social Media and Algorithmic Amplification

Hate speech spreads faster and more virulently online than offline. Platforms like X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, and YouTube prioritize engagement, often pushing extreme content. Despite guidelines, accountability remains weak.

3. Blurred Boundaries

What is “hate” for one community may be satire or criticism for another. Speech laws cannot be overbroad, but they also must not be toothless. Striking this balance is difficult, especially in emotionally charged environments.

Global Comparisons: Learning from the World

- United States: The First Amendment protects nearly all speech, including hate speech, unless it incites “imminent lawless action” (Brandenburg v. Ohio, 1969). This has led to both extreme protection of speech and rising white supremacist rhetoric.

- Germany: Due to its Nazi past, Germany strictly punishes hate speech, Holocaust denial, and xenophobic propaganda.

- United Kingdom: Has a middle-ground approach—protects free speech but criminalizes incitement to racial or religious hatred under the Public Order Act, 1986.

India’s pluralistic society necessitates a tailored approach: we cannot afford the U.S. model of absolute freedom, nor Germany’s high-control model. Our balance must be contextual, responsive, and rooted in the values of dignity, secularism, and social cohesion.

A Way Forward: Redrawing the Line with Precision

- Codify Clear Legal Definitions of hate speech that distinguish it from offensive or controversial opinion.

- Apply Laws Uniformly without regard to political or religious identity of the speaker.

- Strengthen Platform Accountability: Social media firms must respond swiftly and transparently to flagged hate content.

- Promote Counter-Speech and Civic Literacy: Encourage communities and civil society to fight hate with facts and empathy.

- Establish Independent Oversight: An apolitical commission to monitor hate speech cases can ensure integrity and impartiality in enforcement.

Conclusion

Freedom of speech is a sacred right, but it must not become a weapon to silence, intimidate, or marginalize. In a diverse, multi-religious democracy like India, the line between liberty and intolerance must be drawn with clarity, care, and constitutional conscience.

The test is not whether speech is agreeable but whether it is dangerous, whether it invites debate or ignites hatred. To safeguard our democracy, we must defend free expression while relentlessly resisting the normalization of hate.

Contributed by Paridhi Bansal (Intern)