Introduction

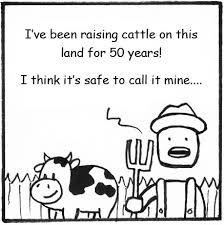

In a world where property rights are held as sacrosanct and deeply personal, the Doctrine of Adverse Possession sits as an anomaly — a legal principle that seemingly allows someone to take over land that is not theirs, and with time, become its lawful owner. To some, it is a justified principle aimed at encouraging the efficient use of land. To others, it is a blatant legal loophole that undermines the core tenets of property law. As with many legal doctrines, the answer lies somewhere in the gray.

What is Adverse Possession?

Adverse possession is a legal doctrine that permits a person who occupies another’s land for a specific period, under certain conditions, to claim ownership over it. The doctrine requires the possession to be:

- Hostile (without permission from the true owner)

- Actual (the person is physically present on the land)

- Open and notorious (the occupation is obvious and not hidden)

- Exclusive (not shared with others, including the true owner)

- Continuous (uninterrupted for the duration specified by law)

The statutory period varies across jurisdictions. In India, for example, the Limitation Act of 1963 prescribes a 12-year limit for private property. In the United States, this period can vary between 5 to 30 years depending on the state.

Historical Origins and Evolution

The doctrine of adverse possession traces back to English common law. Historically, it was rooted in the belief that land should not lie idle and unused. The feudal system encouraged the active use of land, and the absence of a landlord often led to instability. By rewarding those who used and cared for land, the law promoted social order and economic productivity.

Over centuries, this principle was adopted and adapted by various legal systems around the world, with nuanced differences but similar core objectives.

The Case for Adverse Possession: Justified Claim

Supporters of the doctrine argue that adverse possession serves several important societal purposes:

1. Encouraging Efficient Land Use

Land is a finite and valuable resource. When property lies idle for years, it represents a lost economic opportunity. Adverse possession ensures land is put to productive use, whether for agriculture, housing, or commerce. It rewards those who take initiative.

2. Ensuring Certainty in Land Titles

Over time, documentation errors, missing heirs, or unclear boundaries can create legal confusion. Adverse possession offers a pathway to clear long-standing disputes and bring clarity to land records. It protects long-term possessors from sudden eviction and litigation.

3. Promoting Responsibility

The doctrine incentivizes individuals to take care of the land. When someone maintains, improves, and treats a property as their own for years, they demonstrate a de facto ownership that arguably deserves legal recognition.

4. Checks on Inattentive Owners

In many cases, rightful owners abandon land or ignore their duties. Adverse possession serves as a deterrent against such neglect, ensuring owners remain vigilant and proactive about their holdings.

The Argument Against: A Legal Loophole

Critics of adverse possession raise several valid concerns, arguing that the doctrine contradicts the foundational principles of private property:

1. Violation of Property Rights

The most glaring criticism is that adverse possession allows someone to gain legal title without the owner’s consent. It effectively enables land to be taken away from the rightful owner, challenging the inviolability of property rights.

2. Moral and Ethical Dilemmas

The idea that someone can “squat” on another’s land and legally own it over time strikes many as unfair, especially when the original owner may be unaware or unable to monitor the land due to illness, financial constraints, or personal circumstances.

3. Disadvantaging Vulnerable Owners

Marginalized individuals — such as the elderly, people with disabilities, or absentee owners — are at higher risk of losing property through adverse possession. The doctrine may disproportionately impact those who are least equipped to defend their legal rights.

4. Potential for Abuse

There are increasing cases where individuals, sometimes with legal backing, exploit the doctrine to take over valuable land. This raises questions about the safeguards (or lack thereof) in preventing deliberate misuse of the law.

Judicial Interpretation and Reform

Courts across jurisdictions have wrestled with this dichotomy. The Indian Supreme Court, in cases such as Hemaji Waghaji Jat vs. Bhikhabhai Khengarbhai Harijan (2011), has criticized the misuse of adverse possession, urging a relook at the doctrine from a human rights perspective. The court observed that the law seems to reward “dishonest possessors” and penalize genuine owners.

Similarly, in the United States, some states have added requirements such as paying property taxes during the possession period, thus making it harder for opportunistic claims.

There is growing consensus that while the doctrine serves practical purposes, it needs reforms to align with contemporary values and protect vulnerable landowners. Some legal experts propose introducing mandatory notice requirements or mediation before recognizing such claims.

Conclusion: Loophole or Legitimate Legal Remedy?

The Doctrine of Adverse Possession walks a fine line between pragmatism and principle. On one hand, it helps clean up land records, promotes productive use of property, and brings resolution to otherwise intractable disputes. On the other hand, it risks undermining the sanctity of property rights and enabling unjust enrichment.

Whether one sees it as a legal loophole or a justified claim largely depends on the lens through which it is examined — efficiency and utility versus ethics and ownership.

Ultimately, the doctrine’s continued relevance hinges on how well the law balances competing interests. With proper safeguards, clearer definitions, and judicial oversight, adverse possession can evolve from being a controversial concept into a fair tool for managing land in complex legal landscapes.

Contributed By; Tanisha Arora (intern)