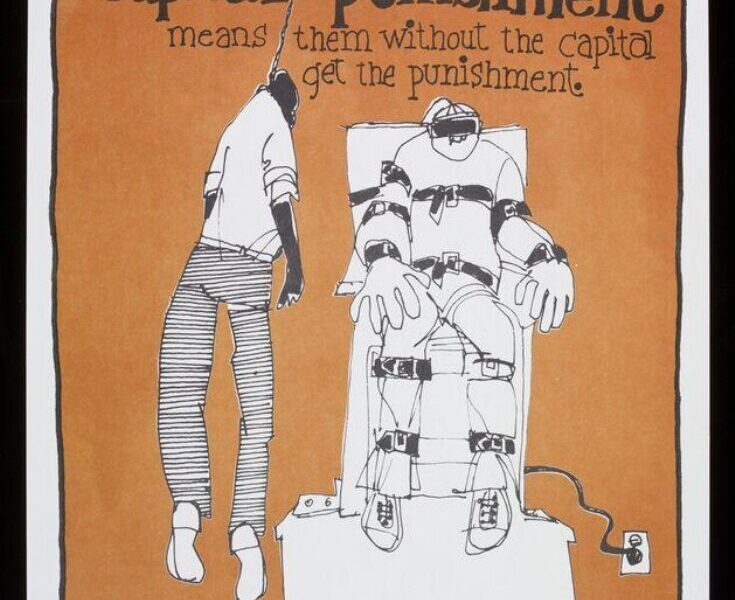

Capital punishment, or the death penalty, remains one of the most debated aspects of criminal jurisprudence, balancing between the demands of retribution, deterrence, and the constitutional guarantees of life and personal liberty. In India, the legal framework governing capital punishment has evolved through legislation, judicial interpretation, and societal attitudes, reflecting a cautious approach to its application. While the death penalty is retained for the most heinous offences, its imposition is now restricted to the “rarest of rare” cases, a doctrine deeply rooted in the Indian judiciary’s effort to harmonise punitive justice with the principles of human rights and proportionality.

The constitutional basis for capital punishment lies in Article 21 of the Constitution of India, which guarantees that no person shall be deprived of life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law. This provision does not prohibit the death penalty per se but requires that the procedure leading to such deprivation must be just, fair, and reasonable. This constitutional mandate has significantly influenced judicial scrutiny over capital punishment, ensuring procedural safeguards and restricting its indiscriminate use.

The Indian Penal Code, 1860, prescribes the death penalty for offences such as murder under Section 302, waging war against the government under Section 121, certain acts of terrorism, aggravated cases of rape leading to death, and some offences under special legislations like the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985. However, the Code also provides the alternative of life imprisonment, leaving discretion to the judiciary to choose between the two penalties based on the circumstances of the case.

A major turning point in the jurisprudence of capital punishment came with the landmark judgment in Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab (1980), where the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of the death penalty but laid down that it should be awarded only in the “rarest of rare” cases where the alternative option is unquestionably foreclosed. The Court emphasised that sentencing must consider both aggravating and mitigating circumstances, including the crime’s nature, the manner of commission, the motive, and the possibility of reforming the offender. This principle has since become the cornerstone of death penalty jurisprudence in India.

In Machhi Singh v. State of Punjab (1983), the Supreme Court further elaborated the “rarest of rare” doctrine, identifying factors such as the extreme brutality of the crime, the magnitude of the offence, and the victim’s vulnerability as relevant considerations. Over the years, the Court has applied these principles to ensure that the death penalty is not imposed mechanically but after a nuanced analysis of each case.

Procedural safeguards are critical in death penalty cases. The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, under Section 354(3), mandates that special reasons must be recorded for awarding the death sentence. Appeals to the High Court are automatic in capital cases, ensuring a higher level of scrutiny. Further, the convict has the right to approach the Supreme Court and to file a review and curative petition. The final constitutional remedy lies in seeking mercy from the President of India under Article 72 or from the Governor of a State under Article 161.

Judicial pronouncements have also addressed issues of prolonged delay in the execution of death sentences. In Shatrughan Chauhan v. Union of India (2014), the Supreme Court held that inordinate delay in deciding mercy petitions can be a ground for commuting the death sentence to life imprisonment. The Court has also emphasised that mental illness or deteriorated mental health of the convict during incarceration is a factor against execution.

The debate on capital punishment in India is shaped by conflicting arguments. Proponents argue that it serves as a deterrent for heinous crimes and delivers justice to victims and society. Opponents counter that there is no conclusive empirical evidence of deterrence, that the death penalty is irreversible and risks executing the innocent, and that life imprisonment without parole can serve as an equally effective punishment without taking life.

The Law Commission of India, in its 262nd Report (2015), recommended the abolition of the death penalty for all crimes except terrorism-related offences and waging war, reasoning that its retention for ordinary crimes was unnecessary and inconsistent with human rights standards. Despite such recommendations, Parliament has, in recent years, expanded the scope of the death penalty, notably through the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2018, which introduced it for the rape of girls below twelve years.

Internationally, there is a growing movement towards abolition, with over two-thirds of countries having abolished the death penalty in law or practice. India, however, remains a retentionist state, applying it sparingly but resisting abolition, often citing public sentiment and the need to deal firmly with certain categories of crimes.

In practice, data shows that while trial courts in India often impose the death penalty, higher courts frequently commute such sentences to life imprisonment, reflecting the cautious approach of the appellate judiciary. The Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in Manoj v. State of Madhya Pradesh highlighted the necessity of a holistic sentencing inquiry, including a background study of the offender, before awarding the death penalty, reinforcing the principle that it should remain an exception rather than the rule.

Capital punishment in India thus stands at the intersection of law, morality, and public policy. The judiciary’s efforts to restrict its application through the “rarest of rare” doctrine and detailed procedural safeguards demonstrate a recognition of the gravity of taking life through state action. Yet, the continued legislative expansion of its scope reveals an enduring tension between human rights advocacy and societal demand for retributive justice. As debates continue, the Indian approach remains one of cautious retention, seeking to reconcile constitutional guarantees with the perceived need to retain the ultimate punishment for the gravest offences.

Contributed By Somya Bharti (Intern)