Introduction

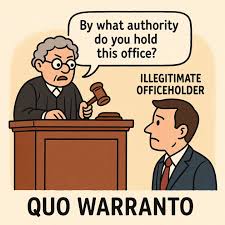

Among the arsenal of writs in India’s constitutional framework, Quo Warranto is perhaps the least discussed yet strikingly potent. While most people are familiar with Habeas Corpus or Mandamus, Quo Warranto remains a powerful but rarely invoked remedy — a unique tool that allows any citizen to question the authority of a person occupying a public office.

In an age where accountability and transparency are paramount, the Writ of Quo Warranto stands as a constitutional safeguard to prevent the usurpation of public offices by ineligible or unauthorized individuals.

What is Quo Warranto?

Quo Warranto literally means “by what authority.” It is a writ issued by a court to restrain a person from holding a public office to which they are not entitled. Unlike other writs which protect individual rights, Quo Warranto protects the public’s interest in ensuring that public offices are not misused.

Historical Roots

The origin of Quo Warranto can be traced to English common law, where it was used by the Crown to challenge feudal lords who exercised privileges or franchises without royal consent. Over time, the concept evolved into a judicial remedy to check unauthorized occupation of public positions.

Constitutional Basis in India

In India, Quo Warranto is provided under Article 226 of the Constitution, which empowers High Courts to issue directions, orders, or writs for the enforcement of fundamental rights and for “any other purpose.”

The Supreme Court too has jurisdiction under Article 32, though in practice, High Courts are usually approached for Quo Warranto as they are courts of first instance for writ jurisdiction.

Conditions for Quo Warranto

Courts have laid down certain conditions for issuing a Writ of Quo Warranto:

- The office must be a public office created by the Constitution or by statute.

- The office must be of a substantive character, not merely ceremonial.

- The respondent must be holding the office without legal authority, or in contravention of statutory provisions.

- Any member of the public, even if not personally aggrieved, can file for Quo Warranto. This makes it a public remedy.

Significant Case Laws

- University of Mysore v. C.D. Govinda Rao (1964)

The Supreme Court held that Quo Warranto can be issued when an appointment is contrary to statutory provisions. - Jamalpur Arya Samaj Sabha v. Dr. D. Ram (1954)

The Patna High Court refused Quo Warranto for a private office, clarifying that it must be a public office. - Hari Bansh Lal v. Sahodar Prasad Mahto (2010)

The Supreme Court reaffirmed that Quo Warranto is a constitutional remedy to prevent usurpation of a public office by ineligible persons.

Scope and Limitations

The writ is limited to examining the eligibility of the person holding the office. The court does not inquire into the merits of administrative decisions made by that person.

Moreover, Quo Warranto cannot be issued against a private office — it must be an office of a public nature. Political appointments like Governors, Election Commissioners, or Vice-Chancellors of public universities are common contexts where Quo Warranto may be invoked.

Why It’s Rarely Used

Despite its potential, the writ of Quo Warranto is rarely used in India. Reasons include:

- Lack of awareness among citizens.

- Preference for PILs and other broader remedies.

- Courts’ cautious approach to not interfere in executive discretion unless clear illegality is shown.

Modern-Day Relevance

In today’s era of increasing politicization of appointments, Quo Warranto remains highly relevant. When eligibility norms for public posts are flouted — for example, appointments without prescribed qualifications or violation of statutory rules — Quo Warranto empowers vigilant citizens to hold public offices to account.

It acts as a check on arbitrary appointments, ensuring that no unqualified person holds a position of public trust.

Conclusion

The Writ of Quo Warranto may appear like an ancient relic, but in truth, it is a timeless safeguard of democratic governance. It embodies the principle that public offices are held in trust for the people, not as private entitlements.

Though rare in practice, its revival in the right contexts can strengthen transparency and uphold the rule of law. After all, in a democracy, the question “By what authority?” must never be out of place.

CONTRIBUTED BY : ANSHU (INTERN)