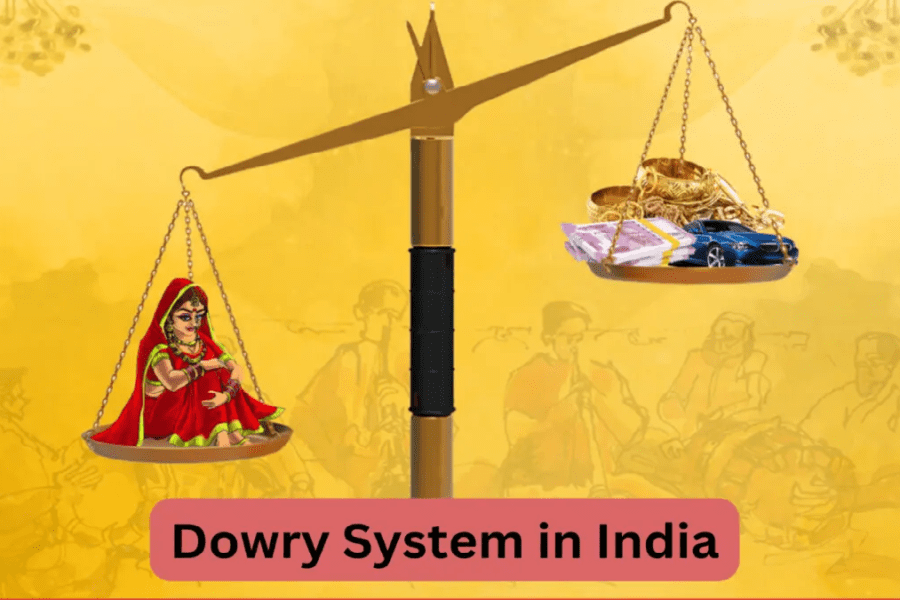

In India, the dowry system remain a persistent social evil, despite being lawed by the dowry Prohibition Act of 1961. Combat dowry related harassment and violence, section 498(A) of The Indian Penal Code was introduced in 1983 of the, empowering women to seek justice against cruelty by their husbands or in-s, particularly in cases involving dowry demands. This provision was intented as a shield to protect women from abuse, but over time, concerns have emerged about its misuse as a tool for personal vendettas, leading to calls for reforms to balance women’s rights with safeguards against false accusation.

The Protective intent of Section 498A :

Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code was introduced to combat the widespread issue of dowry-related violence, encompassing physical, emotional, and mental abuse, which often leads to dowry deaths. According to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), dowry-related issues were responsible for 7,634 deaths in 2015 and remained a significant cause of murder in India, ranking sixth in 2022.

The National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) indicates that 31.9% of married women aged 18-49 have experienced domestic violence, with 80.1% never reporting it, highlighting the underreported nature of such crimes. These statistics underscore the necessity of robust legal protections like Section 498A, which allows for immediate arrests and imposes penalties of up to three years’ imprisonment for cruelty related to dowry demands.

The law’s intent is to provide swift justice to women facing intolerable cruelty, often in patriarchal settings where they lack social and economic power. Women’s rights activists argue that the provision is critical because many victims approach the police or courts as a last resort, facing immense societal pressure to remain silent. The law’s non-bailable and cognizable nature ensures rapid action, which is crucial in cases of genuine abuse.

Misuse of Section 498A: A Call for Balanced Reform:

Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code was enacted with the noble intention of protecting women from cruelty and dowry-related abuse. However, over the years, it has faced criticism for being misused, with false allegations causing severe emotional, financial, and social distress to the accused. The Supreme Court, in cases like Sushil Kumar Sharma v. Union of India (2005), acknowledged this concern, even referring to the misuse of the law as “legal terrorism.”

According to NCRB data from 2012, nearly 200,000 individuals were arrested under dowry-related allegations, yet only 15% of these cases resulted in convictions. While this low conviction rate raises concerns about misuse, it does not conclusively prove that all such cases are false. Structural challenges such as poor investigations, hostile witnesses, or out-of-court settlements often contribute to the lack of convictions.

Striking a Balance: Women’s Rights vs. Misuse Prevention

Achieving a balance between safeguarding women’s rights and preventing misuse of legal provisions requires a nuanced and holistic approach. Some practical measures to ensure this balance include:

- Improved Investigations

Many false cases persist due to inadequate or hurried police work. Appointing and training dedicated officers for handling Section 498A complaints, along with mandating proper verification procedures, can help prevent arbitrary arrests. - Penalties for False Allegations

While protecting genuine victims remains essential, implementing penalties for proven false complaints could deter misuse. For instance, in a 2025 case in Bangladesh, a woman was fined and imprisoned for filing a false dowry case—a model India could consider adapting. - Time-Bound Trials

Prolonged court cases intensify suffering for both victims and the falsely accused. Expedited trials, as advocated by individuals like Gauravjeet Singh Saini, can help reduce harassment and ensure timely justice. - Gender-Neutral Legislation

Laws such as the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, and Section 498A currently do not account for male or transgender victims. Amending these laws to be gender-neutral could address a wider spectrum of domestic abuse and false accusations. - Awareness and Mediation

Promoting public awareness and encouraging mediation in marital disputes can reduce over-reliance on criminal proceedings. The Supreme Court, in Preeti Gupta v. State of Jharkhand (2010), emphasized this approach. Campaigns by organizations like the Seva India Family Foundation, which advocate pre-marriage affidavits declaring “no dowry asked or given,” can also prevent future disputes.

Broader Social and Structural Realities

The issue of false dowry cases cannot be viewed in isolation from India’s social fabric. Despite being illegal, dowry practices remain widespread due to societal pressures. Women who file genuine complaints often face stigma and familial pressure to withdraw, while men falsely accused endure social isolation and mental health challenges, worsened by gender expectations of emotional resilience.

Conclusion

Section 498A continues to be an essential legal safeguard for women facing dowry-related abuse. However, its misuse has led to notable injustices, prompting both judicial and societal demands for reform. The Supreme Court’s evolving guidelines aim to discourage frivolous cases while preserving the law’s protective spirit. A balanced approach—grounded in effective investigations, accountability for false allegations, gender sensitivity, and public education—can help India uphold women’s rights while ensuring fairness and justice for all parties involved.

Contributed by : Sonam Rawat ( Intern )